Uncle Remus in Pictures

November 2011

INTRODUCTION

Striking pictures appear routinely in Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories. Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox provide memorable images in the very first tale, a misadventure with a tar baby (Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings, 1880). The characters are first created with words. We “see” them in our imagination while we read Harris’s text. There are also printed visual images which appear in the pages of the book. These pictures were fashioned by professional illustrators, typically in consultation with the author.

But despite the fact all of the Remus editions were illustrated, for most readers the use of language in these works attracts attention first. Today readers are surprised by Harris’s use of dialect to capture the “real” speech patterns of Southern slaves. The phonetic renderings of the old man’s utterances are discomfiting today.

My co-editors are well equipped to address the language of the Remus materials. I shall attempt to contextualize the visual images which accompany the Remus texts. They provide a rich source, for a number of reasons. The practice of illustration emerged as a profession during the Gilded Age (circa 1870-1900). Not coincidentally the period also saw dramatic improvements in plate-making and printing technology, developments which contributed to the rapid growth of periodical publishing in the United States. Methods of visual realization seen in our sample set of Uncle Remus illustrations cover the technical and stylistic range of the time.

But technology accounts for relatively little of the potential interest of the Uncle Remus imagery. The cultural dimensions of these pictures—that is, the intersection of drawing styles, representations of racial groups, and post-Reconstruction narratives of slavery—command our attention. A cursory viewing of the early Remus illustrations suggests that crude racial characterization also animates the visual dimension of the project. That is, the pictures are also discomfiting for today’s readers.

Though Harris’s own motivations to “humanize” blacks for white audiences were progressive for the late 19th century, and despite the fact that the illustrated editions he controlled were comparatively inoffensive, we’re still brought up short by many of of these pictures. So to what degree should we make these images available, or encourage people to look at them? To some the experience may feel like indulging in a best-forgotten pornography of racism. What’s more, even if one is able to look with a cultural eye, there is a temptation to think that less enlightened viewers will be unable to do so. Such viewers find justification or inspiration for terrible and dangerous ideas.

Despite the discomfort, it is important to look at these images, to better understand our complicated, unsettling and still surprising past. Prevailing attitudes today emphasize commonalities between racial and cultural groups. We have grown ever more alert to the damage that language can do, and we are on guard for it. Yet while the contours of acceptable public speech have changed, underlying private attitudes are harder to make out, and arguably benefit from a direct confrontation with this material. The explicit racism of many Jim Crow era images brings home the reality of our past. They provide a window onto the pervasive ugliness of that comprehensive (yet publicly under-acknowledged) cultural regime.

But we should also strive to view these images historically. That is, there is more to them than what they cause us to feel or think today, from our now distant perspective. For 150 years and more, Americans have struggled to confront, avoid, elide or resolve the legacy of slavery in the United States. Distinctly different but related responses mark attempts to truly come to grips with the near-total extermination of American Indians. Gilded Age iconographies of disdain can be excavated for the urbanized immigrant like the Jew, the Italian, the German and the Irishman. Mexican and Chinese immigrants in the West were likewise subject to pictorial bigotries. The rhetoric of ethnicity was rougher all around and racial ridicule was commonly accepted as part and parcel of a frontier and settler country. But the terms of cultural interchange are always more complex than the simple dualities we fashion to contain them: black versus white, reactionary versus progressive, good versus bad, rich versus poor. Our mongrelized language, traditions and gene pool are proof of enough of that.

Attentively contextual reading and looking can help us understand how, not just that, race and ideas about race have played a dominant, complicated and often tragic role in American history.

Finally, and critically, although we have grown more sensitive to the use and abuse of language in the context of ethnicity and society, we are far less aware of the role of images in public life. Even well-educated persons are not likely to have studied the history of popular images, which do not often appear in the academic discipline of art history. We would do well to pay more attention to the persuasive power of popular images.

UNCLE REMUS AND VISUAL LANGUAGE

Joel Chandler Harris’s Remus books consist of brief allegorical tales interspersed with purported accounts of plantation life. These stories feature colorful characters, and involve a variety of writing and speaking styles. For example, consider the following passage from Harris’s first Remus book, His Songs and His Sayings (1881). In Saying XVII “As to Education” Uncle Remus has an argument with a young boy headed off to school.

As Uncle Remus came up Whitehall Street recently, he met a little colored boy carrying a slate and a number of books. Some words passed between them, but their exact purport will probably never be known. They were unpleasant, for the attention of a wandering policeman was called to the matter by hearing the old man bawl out:

“Don’t you come foolin’ longer me, nigger. Youer flippin’ yo’sass at de wrong color. You k’n go roun’ yer an’ sass deze w’ite people, an’ maybe dey’ll stan’ it, but w’en you com a slingin’ yo’ jaw at a man w’at wuz gray w’en de fahmin’ days gin out, you better go an’ git yo’ hide greased.”

“What’s the matter, old man?” asked a sympathizing policeman.

A reader immediately recognizes that the author narrates in one voice, and that Uncle Remus speaks in another. Harris writes in standard English, and his white characters speak standard English. By contrast, Uncle Remus speaks in an approximation of a Southern black dialect. Others will comment more valuably on what these different textual voices meant to Harris’s audiences. I raise the point to show how easy it is to recognize different voices when one encounters them in a text.

Because most people are not trained to look at images in a fundamental way, typically it’s much harder for viewers to read the differences between visual languages or voices, as opposed to textual ones. To be sure, we can tell a printed illustration from a photograph. But most viewers don’t know how a given image was made, why it looks the way it does, or the degree to which audiences bring contrasting expectations to pictures produced by different image technologies.

In general terms, we can speak of two basic visual languages and professional trajectories in the world of commercial image-making: cartooning and illustration. I will make a brief attempt to define these terms and traditions. For such purposes it will not be necessary to remain within the historical period of the Gilded Age. Examples will isolate key concepts. The reader should keep in mind that the terms cartoon and illustration are being used in two different but related senses. If I mention Illustration A (say, a botanical illustration for a book on herbs) or Cartoon B (say, an editorial cartoon) I am referring to particular artifacts, which are also examples from categories of artifacts. I might also speak of illustration or cartooning as activities, pursuits or professions. In that case I am referring to particular cultural practices, characterized by associated sets of values.

CARTOONING

Cartooning is simultaneously a descendant of, and a more modern designation for, what was called “caricature” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Narrowly speaking, the term “caricature” refers to an exaggerated portrait designed to mock its subject and amuse a viewer. Very early examples are attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. Later, important practitioners in Georgian England integrated such comic portraits into pictures that told stories with captions. James Gillray (1757-1815) pilloried the famous and the vain, while his colleague Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827) practiced a form of social criticism by spoofing the customs and fads of the day. Through diversity of example the term caricature came to indicate a variety of funny pictures. In the mid-nineteenth century cartoon supplanted the term. For practical purposes cartooning refers to image-making in a comic vein, typically addressing social conditions, political figures or the pratfalls of daily life. The term encompasses works for print (comic strips, gag cartoons, editorial cartoons) and animated motion pictures, particularly those grounded in two-dimensional drawing practices.

Scott McCloud observed in Understanding Comics (1994) that cartoons involve simplification and amplification. That is, some things are simplified or flattened out, and others are exaggerated and pumped up.

Barnacle Bill greets Popeye the Sailor. Two panels from a Thimble Theatre strip, December 3, 1933.

Consider Popeye, the comic strip character created by E.C. Segar in 1929. (Segar’s comic strip Thimble Theater debuted in 1919; when the character Popeye made his first appearance in the strip a decade later, he quickly assumed a leading role. Popeye was adapted for animation by the Fleischer Brothers in association with Segar in 1933.) In an animated Popeye cartoon, it’s a given that Popeye and Bluto will battle one another. Their motivations are simple. Popeye wants to go about his business and enjoy the affections of Olive Oyl. Bluto is driven to dominate his surroundings and secure the affections of Olive Oyl—by force if necessary. The two male characters operate almost exclusively on the basis of violent conflict. The given circumstances of the action are very simplified, almost abstract. This provides the creative context for the comedy, which is based on extremely plastic manipulations of the characters—crazy wind-up punches and the like. Segar’s comic strip, while employing a more diverse cast, features similarly elemental conflicts.

The abstract qualities basic to Popeye appear elsewhere. George Herriman’s Krazy Kat (1913-1944), one of the most memorable and broadly influential comic strips of the first half of the 20th century, takes place in a bleak symbolic landscape. Charles Schulz’s Charlie Brown (Peanuts) often sits down on the stoop of his family home. But the stoop isn’t a specific particularized stoop, built of planks or cast from concrete. It’s not a stoop, but the stoop—as symbolic in its way as a set design for Waiting for Godot.

Cartoonists are subject to the values of jest, in both senses of the term: amusement, and mockery. They are accountable to facts only so far as information supports and sharpens the comedy.

ILLUSTRATION

“Illustration” as a word can be chased back to the fourteenth-century France. It carried connotations of spiritual illumination, and was fashioned from a Latin root lustrare (or luster) suggesting the activity of “making bright.” And indeed, the tradition of illustration does carry a sense of shedding light on a text or a certain corpus of content. Contemporary associations with the discipline run toward children’s picture books. And illustrators do make pictures designed to intensify or focus a reader’s experience of a text. But illustrations serve a variety of purposes, including the presentation of information (as in a biology textbook or an automobile manual) and the act of persuasion.

Illustrators see themselves as accountable to the way things actually are, or in alignment with a given body of knowledge or textual source. An anatomical drawing must be accurate to be of any use. An illustration for Moby-Dick must draw on concrete knowledge of whaling, or it will lack authority. Before the widespread adoption of photographic journalism, the visual news of the world was delivered by illustrators working with wood engravers for publications like Harper's Weekly and the Illustrated London News. Illustrators are accountable to the values of reportage, fidelity and non-fiction. The linear portrait illustrations that run on the first page of the Wall Street Journal provide a good example in contemporary terms.

Kevin Sprouls, Portrait illustration of Carl Reiner, 2010.

THE VISUAL VALUES OF ILLUSTRATION AND CARTOONING

The stylistic range of contemporary illustration is extremely broad. But until the middle of the twentieth century, most illustration for books and periodicals was dependent upon traditional figure drawing. That is, most illustration was more or less “realistic” and dependent upon some formal training in draftsmanship. In accordance with values of fidelity and veracity, illustrators used models.

Especially as we prepare to look at the illustrations for the Uncle Remus publications in the Gilded Age, it’s useful to think of illustration as involving formal drawing skill based on European Beaux Arts traditions of drawing and painting. Formal training at that time involved drawing from nude models or alternatively from plaster casts of Roman copies of classical Greek statues. Illustrators were trained as artists first.

Howard Pyle, Bearskin Slayeth the Dragon but will not go with the Princess to the Castle, from The Wonder Clock: Or, Four & Twenty Marvelous Tales, Being One for Each Hour of the Day, 1883.

More specialized training for illustrators did not become available until the mid-1890s, and then for very small numbers of students under the tutelage of Howard Pyle. [note 1]

The supposedly “timeless” values of Beaux-Arts training (associated especially with European academic painting of the 19th century, and “American Renaissance” art from 1880 to 1920) provided illustrators with very important skills. Yet since many would find work on literary projects, extremely time-bound questions like period costumes and technologies posed significant challenges for illustrators striving for accuracy. The apparent veracity of period details were very important, especially for increasingly popular subjects like stories from the American Revolution, neo-medieval subjects, and pirate tales, all of which were booming in the 1880s and 90s. [note 2]

Successful Gilded Age illustrators drew on authoritative sources like prop collections and cast their models very carefully. Many built extensive costume collections.

All of these efforts went toward creating a sense of “real” appearances. This is true not only as a question of period description, but also of visual style itself. Those formal drawing skills were invested in the production of images which looked real. Illustrators stressed three dimensional volumes and recognizable postures and gestures in their characters, even as they often de-emphasized overly complicated environments or settings to make the action of a given story clear. Such strategies still work in our time—a well-fashioned character can be used to distract a viewer from comparatively minimal surroundings which might otherwise introduce doubts about the image. This is especially true when the character has been endowed with an active verb—when the image addresses itself to a dramatic action. But the key point for our purposes here is that the fundamental language of the illustrator’s craft was based on descriptive drawing and the provision of a plausible sense of reality. [note 3]

Despite their reliance on artistic skills, most illustrators did not operate in “the art world.” Illustrators worked for reproduction. They made images designed for mass distribution; the “original” was just a means to get to the printed artifact. Illustrators were required to adapt their approaches to the technologies of platemaking and printing then current at the time of composition. Between the end of the Civil War and the early years of the 20th century, those technologies changed at a stunning rate. What’s more, illustrators’ work has always been frankly contingent on textual sources. For these and other reasons, illustration has never been categorized as art in the normative sense of that term. [note 4] Financially speaking, during the explosive growth in periodical publishing from 1860 to 1940, successful illustrators did very well. Commercial careers could be quite lucrative. But anxiety about status bedeviled many illustrators. Many longed for the recognition associated with the fine arts, yet couldn’t quite say no to the paying work. [note 5]

Cartoonists, by contrast, tend to draw more symbolically than realistically. They use visual languages that are more simple, flat and calligraphic. They emphasize indicative techniques over descriptive ones. (Example: how can an artist show that a character is running? The addition of a set of horizontal “motion lines” is an indication; the choice to render a billowing garment behind the character is a description.) Cartoons from the Gilded Age and today are classified as such because they operate as freestanding units of content. Unlike illustrations, which are crucially contingent upon other material (text or otherwise), cartoons exist on their own terms.

OVERLAPPING PRACTICES

In the Gilded Age, illustration, political caricature and cartooning overlapped to a significant degree. In the early 20th century, when the newspaper comic strip became established as a major cultural form, the cultures of cartooning and illustration diverged sharply.

In the 19th and for much of the 20th centuries, many cartoonists began their careers as tradesmen. Most did not receive formal training. A.B. Frost, one of the foremost humorous artists of the period (and a favored contributor to Harris’s Remus works) began his career as an engraver and lithographer—which means that he did hands-on work in a printing shop. If such people lacked formal training in drawing and painting—Frost had a little, studying briefly under Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy—they taught themselves and each other to tell visual stories to great effect. Frost shared his insights as a draftsman in the early 1880s with the young artist E.W. Kemble while they worked on projects for Life magazine and The Daily Graphic.

Kemble provides a case study in the fluid boundaries between illustration and cartooning. Kemble drew political cartoons for Life from its earliest issue in 1883. Those cartoons attracted the notice of Mark Twain, then preparing to publish The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Kemble was contracted to illustrate the project (1884), and went on to illustrate many books, including Joel Chandler Harris’s On the plantation: a story of a Georgia boy’s adventures during the war (1892). Meanwhile Kemble produced a variety of cartoons and “comicalities” for a variety of magazines and newspapers for the remainder of his career, which continued through the 1920s. His visual approach did not vary greatly between the two pursuits.

BLACKFACE AND THE REPRESENTATION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS

The use of black dialect in Harris’s Uncle Remus works helps to create an image of the eponymous storyteller, establishing his “folk” bona fides. The old man’s diction also points to other racialized performances in nineteenth century America. The popularization of minstrelsy in the 1830s and 40s created a set of stock “voices” for Southern slaves. Its popularity continued even after the Civil War.

Billy Van, the Monologue Comedian, appearing in Wm. H. West’s Big Minstrel Jubilee. Designer uncredited. Minstrel show poster. Strobridge Litho Co., 1900. From the Minstrel Poster Collection at the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Language played an important role in creating representational tropes of blackness. But the visual components of these images can hardly be overstated—blackface most of all. “Blackface” makeup was used by minstrel show performers to transform a Caucasian actor into an African American slave. The simplicity of the procedure is striking: blackened cork was applied to the face, leaving an outsized area around the actor’s mouth—illusionistically magnifying the size of his lips. A tousled black wig established “darky” hair. Colorful but shabby costuming completed the picture. William H. West’s Minstrel Jubilee poster captures the contrast nicely: the refined Billy Van, chin up, in repose at left; and the childlike, electrified darky clown at right. Same man, different modes. [note 6]

Blackface accomplished an erasure of subtley in some respects while intensifying contrast in others. The particularities of human physiognomy were leveled by the cork, just as a spraycoat of matte black on a form flattens our perception of it. But the contrast between the carbon-black face, exaggeratedly large pink “lips”, bright “google” eyes and white teeth converted a person into an animated symbol. McCloud’s cartoon dictum applies: simplification meets amplification. Blackface, then, amounts to a live-action cartoon.

It was just this comic simplification of human form that gave blackface its power to travel to other media. Memorable, resonant, the convention acquired “legs.” Black face, google eyes, clown mouth: the representation would not require professional training. As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, the visual descendants of blackface would include gollywog dolls (bug-eyed woolen figures) and early animated characters.

Hugh Harman, character design for Bosko, Warner Brothers Animation, 1933.

In the 1920s and 30s, creators of animated cartoons used graphic simplification to streamline the production process. The visualization of Felix the Cat, for example, echoes the high contrast of blackface characterization. (Felix, produced and promoted by Pat Sullivan, drawn by Otto Messmer, debuted onscreen in 1919 and became an animated celebrity in the next decade.) Disney’s Mickey Mouse follows in this vein, and explicitly references minstrelsy in the early shorts, getting a faceful of stove soot in “The Birthday Party” (1932). The Warner Brothers’ Bosko—the early franchise player on the Looney Toons team—draws on the same visual tradition and speaks in Southern black dialect in his first short (1930). Harman-Ising, the team that created Bosko, went on to produce a jazz short called “The Old Mill Pond” (1936) featuring frogs as blackface performers which included musical contributions from Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller and Cab Calloway. Walter Lantz’s Scrub Me Momma with a Boogie Beat (1940) populates an entire town with blackface characters with traits derived from minstrelsy. And Disney’s Dumbo (1941) features a quintet of crows who speak and sing in dialect, making reference to a parallel tradition in the representation of blacks, that of (Jim) crows. Any such discussion must reference the ultimate convergence of Joel Chandler Harris and cartooning: the Disney film Song of the South (1946), now regarded as an embarassment by the studio. [note 7]

The stress on racial characterization gives blackface its ugly inflection. As comic devices, bug eyes, clattering teeth and the use of broad acting styles to convey emotion can be quite funny. (Don Knotts, the comic actor who played Barney Fife on The Andy Griffith Show built a career on these devices.) The transition from blackface references in early animation to racially neutral character designs a generation later suggests that the racial give-and-take of minstrelsy migrated to cartooning, then faded. A case can be made, in fact, that the visual convention of blackface contributed to the development of the visual language of modern cartooning, which emerged toward the end of the 19th century in Europe and America. That process was driven by an exploding demand for illustrated entertainment, photomechanical plate-making techniques, fast work on tight deadlines, and aesthetic innovation.

JIM CROW AND VISUALIZED SUBJUGATION

In 1877 the federal policy of Reconstruction ended, and the U.S. Army withdrew from Southern states. Gains by blacks were quickly reversed, and the white majority of the vanquished Confederacy reasserted the old racial order. The end of slavery had been accomplished. But new forms of legalized oppression were designed to limit the prospects of blacks. These new codes went by the name of “Jim Crow” laws. The negative effects of the Jim Crow legal regime were augmented by extra-legal practices designed to terrorize blacks. Freed slaves and their families lived under siege, their positions radically circumscribed.

It seems a special cruelty that in the shadow of slavery, under post-Reconstruction cultural assault, Southern blacks should have been presented as shuffling, shabby fools who were better off on the plantation; worse, that they were portrayed as nostalgic for slavery. But the myth of the satisfied slave survived as a holdover from antebellum minstrelsy, and served to assist Southern whites in the construction of an alternate cultural narrative in the aftermath of the war. According to which slavery might retroactively be characterized as a beneficent regime, as opposed to the horrendous historical fact of the thing itself. Whiffs of such sentiment waft through Joel Chandler Harris’s accounts of plantation life in the Remus literature, and help to explain the books’ popularity among Southern whites.

Dissociation from slavery-as-sin was well served by characterizations of freed blacks as buffoons. The visual history of the Jim Crow era demonstrates the degree to which the market rose to meet that challenge.

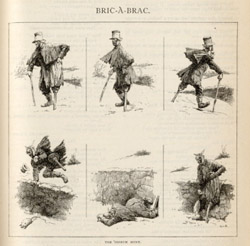

E.W. Kemble, Bric-à-Brac, captioned “The 'Possum Hunt,” Century Magazine, June 1890.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was excerpted in the new Century Magazine. On the strength of his illustrations E.W. Kemble became known as a “negro” illustrator (that’s of, and not by). Throughout his career, depictions of blacks were alternatingly sympathetic (often, when illustrating someone else’s text) and egregious (typically, when publishing his own material). In 1890 Century sent Kemble to Georgia to observe Southern folkways. In a piece published that same year captioned “The Possum Hunt,” Kemble presents a clownish black man with a peg leg, top hat and fraying shawl scrambling to catch a possum by its tail for his dinner. The pursuit requires six frames in a comic strip-like configuration. Otherwise accurately proportioned, the man’s facial features are pure gollywog, meaning they resemble the woolen dolls of the same name popular at the time, based on blackface conventions. Kemble the cartoonist delivers the joke his audience knows to expect: the comical degradation of the hapless negro. (Is there a lowlier meal than the opossum, consumer of garbage?) Kemble’s image drew on existing tropes; in Harris’s first Remus text a comparable simile is offered: “es proud ez a nigger widder cook ‘possum,” and the trope probably dates to antebellum minstrelsy. (His Songs and His Sayings, 1880, p. 53.)

The early Jim Crow era overlapped with an explosion in illustrated entertainment, especially in the burgeoning newspaper business. The advent of effective, cheap color printing helped to create the phenomenon of the Sunday comic supplement, which made its first appearance in the mid 1890s. R.F. Outcault created the famous Yellow Kid as part of the tableau of Hogan’s Alley, a raucous full page feature in the New York World. Outcault delivered a comedic portrait of working class mayhem on the Lower East Side, in the process helping to launch the comics as an enterprise, though Hogan’s Alley was not structured like a comic strip. The Yellow Kid had friends, among them Lil’ Mose, a black child of similar age. Outcault, unable to merchandise the Kid for lack of copyright, forsook the feature when his contract ran out. He went on to create Buster Brown, a new character he owned outright, in 1904. From time to time, Lil’ Mose showed up in Buster Brown strips, as well as advertising material Outcault developed for his merchandising partners, like the Brown Shoe company.

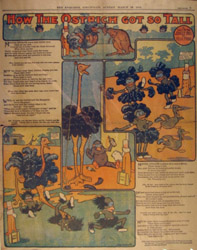

Winsor McCay, How the Ostrich Got So Tall, an episode of Tales of the Jungle Imps, Cincinnati Enquirer, March 29, 1803.

In 1903 Winsor McCay developed a comical feature titled A Tale of the Jungle Imps by Felix Fiddle for the Cincinnati Enquirer. The feature tracked the exploits of dark-skinned mischevious jungle imps, costumed in grass skirts and anklets, who possessed antic personalities and enormous lip regions in the manner of blackface makeup. The imps tormented various African animals, but were always outwitted by the bearded Dr. Monk. In the March 29, 1903 feature, short-necked ostriches with pompadour headdresses are plucked by rampaging imps. Dr. Monk devises a comedic neck-lengthening procedure, helping the birds outgrow their opponents.

A year later McCay would move East, to create Little Nemo in Slumberland for the New York Herald. An African character named Impy, a holdover, would resurface in some of the most memorable Nemo strips. McCay’s imps combine the tradition of blackface minstrelsy with garbled images of and condescension to Africans.

The visual vocabulary of blackface lived a long life in the nation’s comic pages, surviving into the 1940s. If Outcault, McCay and later cartoonists used the visual vocabularies of blackface, these are unremarkable facts. More notable is the sheer volume of illustrated ephemera—advertisements, postcards, knick-knacks, whatnot—that used degrading visual tropes to characterize blacks as lazy, leering subhuman idiots. Properly understood, these materials should be seen as core samples extracted from American cultural history between 1800 and World War Two, showing randomized but comprehensive evidence of attempted racial subjugation—and not only in the South.

USES AND ABUSES OF CHARACTERIZATION

Distinctions must be drawn between a) the typological communication fundamental to cartooning when based on individual characteristics, and b) the use of the same techniques to capture purported qualities of a group.

In good cartooning, a character looks like what he is. Bluto, for example, looks like a big bully.

Other cases involve the visualization of moral characteristics. The Queen in Disney’s Snow White (1937) concocts a potion to disguise herself, to facilitate the murder of her rival. For the audience, the effect of the Queen’s procedure is to reveal her "true" self. Cartooning does the work according to conventions of witches and hags, a slide into associations with older, single women. (Feminist readings of this text suggest themselves.) But for the purposes of this discussion, the bent-backed hostile witch looks the way she does as a representation of the Queen’s inner ugliness.

The simplification and amplification of cartooning do the communicative work of establishing relevant traits of individual characters. Such characterization tends toward the essentialist and categorical—the bashful girl, the intolerant father.

But the essentializing techniques which work so well for characters in a cartoon often prove disastrous and dehumanizing when deployed on a group. This gets to the heart of why blackface seems so disturbing today. Ethnic generalization tends to be negative. “They’re all like that,” is a dangerous sentiment, no matter who “they” are. The techniques of cartooning are deployed to simplify a diverse group, to flatten them into stereotypes.

The distinction between pictorial bigotry and legitimate character differentiation requires significant reflection and a great deal of care. For example: illustrators in a contemporary pluralistic culture are often asked to adjust the ethnicity of a character. One often hears, “Make that guy African-American,” or “Can one of these people be Asian?” The procedure requires the adjustment of features and hairstyles in subtle ways. The illustrator in this case trades on knowledge of physiognomy and ethnicity. It’s not that physical differences don't exist—it’s how they are reported and manipulated, and to what end.

ILLUSTRATED HEROES AND CARTOONED VILLAINS

Adventures of the Young Pioneers (directed by Vladimir Pekar, 1971) is a Soviet propaganda film which contemplates life in a Russian town under Nazi occupation during World War Two. [note 8] The pioneers of the title references a young people’s organization comparable to the Boy Scouts. The Germans who run the town are buffoons, yet also engage in terrible activities like book-burning. The young pioneers are the heroes of the story.

In a surprise twist, the Nazis are assisted by a collaborator, a Jew who lives in the town. We know the man is Jewish because of his peasant costume and clownish appearance.

The kids are drawn in correct proportion, with properly scaled limbs, heads and facial features. In the world of the film, they obey the conventions of illustration. Their faces are somewhat frozen-looking; they’re even a little creepy.

By contrast, the Germans are drawn with big noses, short legs and drooping helmets. [note 9] The Jew is plump, also with a big nose. He dresses up as a woman to confuse the pioneers, and later climbs a roof to spy on them.

Ultimately the Nazis are foiled when a Soviet plane, summoned by the pioneers’ red scarves, bombs enemy headquarters. Subsequently waves of bright red Soviet tanks roll into town, saving the day. A heroic-looking soldier, also properly proportioned, emerges from the tank as flags wave.

The contrasting visual conventions of the Soviet kids versus the Germans roughly match the conventions of the white characters versus the black ones in the Remus literature. [note 10] The young pioneers and the plantation owners are properly drafted. The Germans and the slaves are cartoonishly drawn, and somewhat foolish-looking. The first group is boring. The second group is interesting.

The illustration work in the early Remus books contain somewhat less internal contrast than do the character designs in the film, but not by much.

Frederick S. Church, Miss Meadows En De Gals. Illustration from Uncle Remus, his songs and his sayings; the folk-lore of the old plantation. By Joel Chandler Harris. NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1881. Page 82.

Frederick S. Church, Miss Meadows and the Gals with Brer Rabbit and Brer Tarrypin. Uncaptioned illustration from Uncle Remus, his songs and his sayings; the folk-lore of the old plantation. By Joel Chandler Harris. NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1881. Page 53.

The graceful Beaux-Arts drawing of the white characters can be usefully compared to the gnarled, exaggerated renderings of Remus, other blacks, and the animal characters. This contrast of draftsmanship appears in the very first works, and must reflect authorial intent given Harris’s level of engagement in the project. To take a pronounced example: representations of Miss Meadows and “the gals” obey conventions of neo-classical figurative painting and sculpture. They are costumed in long sleeveless dresses and assume retiring poses. Frederick Church presents the trio as a central group flanked by Brer Rabbit and Brer Terrapin in an untitled illustration for Brer Terrapin Comes on the Scene. The depiction of the women suggests classical pretensions to timelessness, a Three Graces of the Plantation. And an image captioned Miss Meadows en de Gals shows one of the women in a languid version of the contrapposto pose assumed by the Doryphorous by Polyclitus, or the Venus de Milo, or Michaelangelo’s David. Church had received formal art training in New York; the references weren’t accidental.

Frederick S. Church, Uncle Remus, Daddy Jake, and Little Boy. Uncaptioned illustration from Nights With Uncle Remus: Myths and Legends of the Old Plantation with Illustrations, 1883.

In a subsequent Remus project, Church provides a case study in divergent visual voices for whites and blacks in a single image. In an uncaptioned illustration for Nights With Uncle Remus. Myths and Legends of the Old Plantation with Illustrations (1883) he presents Daddy Jake, Uncle Remus and a little Caucasian boy in an intimate configuration. Uncle Remus, at left, supports the boy, hands at his back; the boy, daintily attired and utterly calm, gives his hands to an imploring Daddy Jake, seated before him at right. Consistent with the classical and Renaissance sources on which the Beaux-Arts tradition drew, the boy has the grace and self-possession of an angel. The ancient negroes, by comparison, are gnarled like old trees. Remus’ eyes are wide. Their mouths hang open. Their limbs are stick thin. Hands and feet have been enlarged. (Because Church has modeled all three figures—by which I mean to say he has built a tonal thicket of hatched lines, endowing them with an illusion of volume—it is possible that the uninitiated viewer might miss the contrasting approach to realizing black and white characters.) Finally, the composition drives our attention to the boy, whose elegance is heightened through contrast.

Representations of Drusilla in particular seem to grow more racialized as time passes. Some of the most dramatic and appalling variation in racialized drawing may be found in Harris’s Mr. Rabbit at Home: A Sequel to Little Mr. Thimblefinger and his Queer Country, 1895. The illustrations by Oliver Herford show how frank the diverging conventions got: in “How did you get here,” two elegant white children bend over a stump to address the eponymous small man; Drusilla, uninvolved, agape, absurd, has been dropped into the picture as if through a trap door from an in-progress minstrel show. The most charitable accounting for Herford’s pictures in this edition would be laziness, both in conception and execution. His reliance on convention should be distinguished from the craft of his drawings, which are quick to the point of carelessness. But he did little better the next year, in an edition of Harris’s The Story of Aaron: (So-Named) The Son of Ben-Ali: As Told by His Friends and Acquaintances.

As a matter of textual voice and realization of character, Harris’s Remus brings imagination and memorable figures of speech to his narration, despite its homeliness. The white characters, well-spoken though they be, do little but provide a foil to the old man. The Soviet propagandists reserve right-thinking and -acting for the Young Pioneers, and give all the comic bits to despised Jews and Germans. The comparison yields a paradox: in both cases the producers control the narrative and determine the visual signature. But both cede interest to the mocked weaker party.

ANIMALS, HUMANS AND CARTOONS

The animals that appear in the illustrated Uncle Remus literature travel an arc, from a kind of realism (traditionally drafted rabbits who walk bipedally) to modern animated character design (say, in Disney’s Song of the South), with many steps in between. The historical period of composition has something to do with this range. Modern cartoon drawing styles developed during in the last third of the 19th century, partly in answer to increasing demand for illustrated entertainments. Simplification born of speed and repetition assisted in the process.

Visually speaking, it’s a long way from Peter Rabbit to Bugs Bunny, though an anthropomorphizing instinct drives both. This section will be expanded in coming months.

PRINTING AND PLATEMAKING 1860-1910

The Uncle Remus publications were issued during a period of rapid development in platemaking and printing technology. A summary of these changes will be provided in this space in coming months.

1 Pyle was an illustrator, writer and early “star” in the world of commercial images. Pyle, then living in his hometown of Wilmington, Delaware, approached the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts with the idea of offering a course in illustration. He was rebuffed. Pyle went to Drexel University with the same idea, and the parties agreed. The course ran in 1894-95. Pyle later founded his own private school of illustration in Wilmington. The group summered in the Brandywine Valley in Southeastern Pennsylvania; Pyle and his followers subsequently became known as the Brandywine School of American illustration. His students included such luminaries as N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, Jessie Willcox Smith, and Harvey Dunn. [back]

2 And all of which were associated, to one degree or another, with Howard Pyle. His most significant work falls roughly into three subject categories. 1) Medieval romances, including, especially his own version of Robin Hood with illustrations, from 1883, which remains the preferred text; 2) serial pirate stories and articles, including The Rose of Paradise (1887), famously “Dead Men Tell No Tales,” in Collier's in 1899, and The Ruby of Kishmoor (written in the 1890s, published in 1907); and 3) works of American history, from the early Colonial period through the Civil War era. A meticulous researcher, Pyle illustrated Harper’s articles by Woodrow Wilson on the Revolutionary era, and famously corrected the future president’s texts in spots. Pyle’s visualizations of trappers, frontiersmen, soldiers, and other types—to say nothing of his reconstructions of historical events, like the Battle of Bunker Hill—became accepted historical fact and lodged in the American consciousness. Likewise, his visual treatments of buccaneers and pirates very quickly became archetypal figures in the popular mind, influencing subsequent illustrators and film directors. [back]

3 It’s important to note that over time, and especially after 1950, cartoon drawing styles made their way into the field of illustration. Today, illustration covers an extremely broad range of style and media. But veracity remains a prime value. Nowadays, fidelity doesn’t entail a particular visual style. A simplified or flattened-out drawing approach might work particularly well to explicate a given text. In other words, the contemporary illustrator isn’t necessarily faithful to appearances, but rather to content. [back]

4 With rare exceptions, standard-issue art history courses do not address or include illustration, and art museums do not exhibit it. There are sound philosophical reasons for the exclusion, based in eighteenth century aesthetics and the modern conception of the art object. Scope does not permit that discussion here. See: Immanuel Kant and disinterest theory. [back]

5 The illustrator N.C. Wyeth wrote in a letter to his mother, “I don’t want to be rated as an illustrator trying to paint, but as a painter who has shaken the dust of the illustrator from his heels!!” He wrote that letter in 1915, four years after his landmark illustrations for the Scribner's edition of Treasure Island set the terms for an extremely successful career. He worked steadily in illustration for the rest of his life. The conflicted, self-loathing illustrator is practically a stock type. (Ironically, Wyeth’s illustration work was sharp, colorful, innovative; his paintings were often stale and backward-looking.) [back]

6 The minstrel show emerged in the 18th century, but blossomed into a full-blown musical form in the 1830s. Minstrel shows featured comic oratory, funny skits, song-and-dance numbers, and sendups of serious dramatic literature. They were popular in the North as well as the South. Most significantly for later culture, the form established stock types: the dimwitted but happy-enough slave, the black dandy, the mammy, and others. These images, created by whites in blackface, and decades later refined by blacks in blackface, would prove distressingly durable. Minstrel shows were gradually supplanted by vaudeville acts after the turn of the 20th century. [back]

7 Disney has never released the film for the home video market in the United States. Song of the South appeared just before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball (1947) and not long before President Harry Truman ordered the integration of the armed forces (1948). While Song combined live action scenes with animated interludes to illustrate Uncle Remus’s stories, the objectionable portions of the film are concentrated in the live action sequences. Uncle Remus (played by James Baskett) and the children he entertains have been transported from an imaginary sunny Southern past—suggested by Harris, to be sure—but more egregious for any lack of adjustment in Disney’s version more than 65 years after the first Remus work was published. In retrospect, the studio’s sense of timing—especially given well-publicized discussions between the NAACP and Hollywood producers concerning representations of blacks in American cinema in 1942—could scarcely have been worse. [back]

8 Adventures appears in Animated Soviet Propaganda: From the October Revolution to Perestroika, a four-disc compilation issued by Soyuzmultfilm in 2007. [back]

9 The mystery of why a World War Two-themed propaganda film should have been produced in the Brezhnev era can be answered in two words: Schultz and Hochstetter. For the initiated, the film’s clumsy Wehrmacht soldier and scowling Gestapo officer owe an obvious debt to characters in the American television show, Hogan’s Heroes [CBS, 1965-1971]. Sergeant Schultz, played by John Banner, and Major Hochstetter, played by Howard Caine, are exaggerated live action figures who lend themselves to cartoon treatments—providing another example of easy movement between character actors and cartoon drawings. [back]

10 Admittedly, The Young Pioneers is a piece of government-funded agitprop, while the Uncle Remus books are commercial products with propagandistic aspects. The two works are separated by almost 100 years. Pioneers draws on modern cartoon vocabularies which did not exist in 1880. But the cultural comparison isn’t so far-fetched. During the late 19th century, blacks in the American South lived in a de facto totalitarian state. Their options were that circumscribed; their recourse in the face of brutality that hopeless. [back]