The Brownies’ Book and the Roots of African American Children’s Literature

As a reader can observe from other material in "The Tar Baby and the Tomahawk: Race and Ethnic Images in American Children’s Literature, 1880-1939," visual and literary degradations of black children pervaded popular culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In literature, illustration, minstrelsy, and material culture, black children were fodder for horrific caricatures that constructed children as uncivilized savages, akin (and prey) to animals, and isolated from any parental or familial framework. What was the response within black children’s literature? What factors caused black children’s literature to develop? What was the earliest major text for black children? Answers to these questions are still emerging, as scholars develop ideas and discover new sources of children’s literature from within the African American community. One important site of origin for black children’s literature is certainly W. E. B. Du Bois’s work at the Crisis magazine and his publication of the first major, extant periodical for children, The Brownies’ Book (1920-1921).

Born in Massachusetts in 1868, Du Bois attended Fisk University as an undergraduate and Harvard University for his graduate work, becoming the first black person to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard. In one of his most important early books, The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois articulated the idea of black "double consciousness," the awareness of being seen through the viewpoint of white America: he explains, "It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two warring souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder" (3). Du Bois in the 1910s also believed that social transformation would come through the leadership of the "Talented Tenth," race men of good character who had been educated in a liberal arts tradition and who would bring the other ninety percent of black America into citizenship and modernity. Du Bois supported equal civil rights for African Americans and worked with fervor to support legislation prohibiting the practice of lynching. In 1910, Du Bois helped found the interracial National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and began editing its monthly magazine, the Crisis. Du Bois published in the magazine passionate and influential editorials advocating for civil rights; the publication also contained poems, stories, illustrations, photographs, sociological essays, and journalistic coverage. Key to understanding the emergence of black children’s literature is an awareness of the political courage of the Crisis under Du Bois. In an era riddled with racial prejudice, social and legal injustices, and horrific campaigns of hate, Du Bois used the Crisis in order to draw national attention to America’s failure to live up to its promise of equality for all. In 1920 as an extension of his work at the Crisis, Du Bois launched the first major African American children’s magazine, The Brownies’ Book, which founded the field of black children’s literature.

However, Du Bois was not the first African American editor to address black children as an audience. A few earlier magazines appeared, including Our Women and Children, a Baptist publication out of Louisville, KY, in the 1880s, which included contributions by Mary Britton, Gertrude Mossell, Amelia Tilghman, and Victoria Matthews. In the late 1880s, Amelia E. Johnson, author of Sunday school fiction, published a short magazine for young people titled The Joy. Unfortunately, scholars have not been able to locate copies of Our Women and Children or The Joy, a situation that is not uncommon in the case of ephemeral newspapers and magazines. Du Bois’s journal, The Brownies’ Book , appeared at the tail-end of one of the most productive moments for black periodicals. As Jean Marie Lutes notes, "Between 1895 and 1915, more African American newspapers — some twelve hundred — were launched than in any other era of American history" (337). Just because scholars have not located copies of children’s magazines from the African American community before The Brownies’ Book does not mean that they didn’t exist. In fact, The Brownies’ Book participates in the blooming of black magazines and newspapers during the early twentieth century. Many of the periodicals listed in the most comprehensive bibliography of black magazine publishing, James Philip Danky’s African-American Newspapers and Periodicals: A National Bibliography, include a children’s column and parenting advice. Scholars have yet to investigate fully the role of periodicals to the eruption of black children’s literature in the 1920s, but the prominence of the Crisis and The Brownies’ Book are indicators of a lively print culture interest in black childhood.

Another key factor in the birth of black children’s literature in 1920 was the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance, a period which scholars loosely bracket as occurring between 1917 and 1937. Images of exuberance and creativity characterize the Renaissance in the popular imagination: this was the "jazz age," the era of Duke Ellington and Fats Waller; this was the moment when "Harlem was in vogue" as white people journeyed to upper Manhattan in order to participate in the lively club scene, and when white patrons and publishing houses supported black literary artists like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. For the average African American, the Harlem Renaissance offered a new sense of hope and the possibility of cultural reinvention, as masses of black people moved from the rural South to the urban North with ambitions for a better life. They had already endured the injustices of Reconstruction, the terror of hate campaigns like lynching, and the shock of pervasive racism upon the return of veterans from Europe after World War I. Harlem — as well as Washington, D.C., Chicago, Philadelphia, and other urban sites — offered the possibility for economic success, political equality, and social change. This era of hope and transformation was also referred to as the "New Negro" movement, as intellectuals, artists, and the average person aimed to reconstitute African American identity and citizenship. It is no wonder that the goal of social transformation would include the reclamation of black childhood from the defamations of a racist white popular culture. As the newest of "New Negroes," black children would embody the representational and conceptual innovations of the Harlem Renaissance.

In an editorial in the Crisis in October, 1926, W. E. B. Du Bois writes, "There is a real sense in which the world is growing young; and that is the reason we are paying more attention to the Youth, the Child, and the Baby" ("Crisis Children" 283). Du Bois understood that the Harlem Renaissance, one of the greatest periods of black cultural reinvention, involved and implicated young people. Children would carry into the future the ideals of progressive black thinkers like Du Bois, as well as the dreams and ambitions of their parents and the larger community. The Crisis’s annual October Children’s Number and its offshoot, The Brownies’ Book , became the foremost avenues for dialogue about the possibilities for black youth in a new era. Although Du Bois in an editorial would refer to children as "embryonic men and women" ("Discipline" 270), in fact the black community, particularly the middle class, struggled to define its relationship to youth, as the ambition to create race leaders collided with the longing to insulate children from prejudice and hatred. The Brownies’ Book arose as a response to Du Bois’s desire to balance racial self-respect with protectionism. By exploring the origins of the children’s magazine, this essay addresses the relationship of the Crisis to The Brownies’ Book and explores the distinct contributions of the children’s magazine as the first major publication in black children’s literature.

Several factors contributed to the cultural ascendance of black childhood in the

1920s. First, the racial uplift movement helped reposition attention towards

childhood, since the black elite in the 1900s and 1910s offered parenting

directions in women’s club publications and in conduct books. Proper parenting

became a form of civil rights activity, as it produced well-behaved, refined,

upper-middle class children who demonstrated black cultural and material success

[note]. Second, the eugenics movement permitted Du Bois and

others to appropriate the rhetoric of physical and intellectual superiority in

order to evidence the vigor and dynamism of black childhood, in opposition to

the defamations of racial pseudoscience [note]. Throughout the 1910s and

1920s, Du Bois included on the pages of the Crisis

hundreds of photographs of African American babies and small children in order

to document the progress of the race through the health and beauty of the black

child body.

Figure 1, Crisis, Oct. 1918.

In Figure 1, published in the October 1918 issue, Du Bois arranges a

number of images of healthy, beautiful, affluent children. One child sits before

an open book, and others play violin and piano, all signifying black America’s

embrace of education, Western cultural ideals, and parental care.

Figure 1, Crisis, Oct. 1918.

In Figure 1, published in the October 1918 issue, Du Bois arranges a

number of images of healthy, beautiful, affluent children. One child sits before

an open book, and others play violin and piano, all signifying black America’s

embrace of education, Western cultural ideals, and parental care.

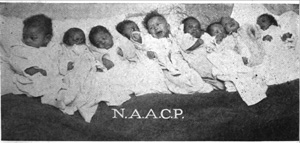

Figure 2, Crisis, Oct. 1922.

Figure 2,

published in October 1922, offers another typical arrangement; while these

middle-class children appear at a closer focus than those in Figure 1, and as a

result lose the signification of their surroundings, Figure 2 includes a larger

number of attractive, well-tended children, and adds the details of their names,

cities, and states. The effect here for Du Bois is to suggest the range of black

cultural accomplishment. The "New Negro" child is not particular to New York

City, but also populates cities and towns in the Midwest and the South, and

extends even into Liberia in Africa. The image demonstrates evidentiarily the

success of this new image of black childhood, one that stands in clear

opposition visually to the caricatures of minstrelsy, cartoons, illustrations,

and film. In truth, black newspapers had been for decades using positive

photographs of children in order to make a case for black vitality and

citizenship.

Figure 2, Crisis, Oct. 1922.

Figure 2,

published in October 1922, offers another typical arrangement; while these

middle-class children appear at a closer focus than those in Figure 1, and as a

result lose the signification of their surroundings, Figure 2 includes a larger

number of attractive, well-tended children, and adds the details of their names,

cities, and states. The effect here for Du Bois is to suggest the range of black

cultural accomplishment. The "New Negro" child is not particular to New York

City, but also populates cities and towns in the Midwest and the South, and

extends even into Liberia in Africa. The image demonstrates evidentiarily the

success of this new image of black childhood, one that stands in clear

opposition visually to the caricatures of minstrelsy, cartoons, illustrations,

and film. In truth, black newspapers had been for decades using positive

photographs of children in order to make a case for black vitality and

citizenship.

Figure 3, Colored American Magazine, Nov. 1900.

Figure 3 shows an image from Pauline Hopkins’s Colored American Magazine titled "The Young Colored American." First

appearing in October 1900, this image was sold as part of a subscription to the

magazine, and pictures a genuinely optimistic vision of black childhood at the

turn of the century. Black families displayed this photographic poster in their

homes, signaling the culture’s new attitude towards the potential of young

citizens. As the child perched on the flagpole points upward, the image suggests

that the sky is the limit for black American youth. The Crisis and Brownies’ Book images, then, did not

emerge in a photographic vacuum. Black periodicals had previously been employing

images of children in order to indicate cultural commitment to citizenship,

futurity, and possibility.

Figure 3, Colored American Magazine, Nov. 1900.

Figure 3 shows an image from Pauline Hopkins’s Colored American Magazine titled "The Young Colored American." First

appearing in October 1900, this image was sold as part of a subscription to the

magazine, and pictures a genuinely optimistic vision of black childhood at the

turn of the century. Black families displayed this photographic poster in their

homes, signaling the culture’s new attitude towards the potential of young

citizens. As the child perched on the flagpole points upward, the image suggests

that the sky is the limit for black American youth. The Crisis and Brownies’ Book images, then, did not

emerge in a photographic vacuum. Black periodicals had previously been employing

images of children in order to indicate cultural commitment to citizenship,

futurity, and possibility.

A third factor contributing to the rise of interest in black childhood in the first decades of the twentieth century had to do with urbanity. As the great migration drew families from the deep South to cities in the North, young people found themselves in new spaces with new vistas. Children shared in their parents’ commitment to modernity and economic possibility. Finally, longstanding African American dedication to education gained traction during the 1920s, as black children became increasingly invested in the authority of the printed word and the classroom [note]. The Harlem Renaissance thus transformed expectations for black childhood by drawing on the energies of the revolutionary moment. Children had always been important within black families and communities, of course; the popularity in recitation of poems like Paul Laurence Dunbar’s "Little Brown Baby" attests to the African American community’s desire to see in art a reflection of the deep affection between parents and children. However, it was in the late 1910s and early 1920s that the public image of black childhood shifted dramatically, and Du Bois at the Crisis helped spearhead the black civic commitment to children as embodiments of social change and possibility.

Du Bois proclaims in his 1926 "Crisis Children" editorial, "Few magazines have tried to do more for the children than The Crisis" (283). Indeed, the magazine under Du Bois’s leadership devoted much space and attention to issues concerning youth, including his influential editorials on education and parenting. The annual Children’s Number appeared each October from 1912 until shortly after Du Bois’s departure from the Crisis in 1934, offering a fascinating miscellany of material connected to childhood: from reports on education and child health, to photographs of children and young adults, to poetry, illustrations, and short stories both addressing young people and concerning the situation of parents, the Children’s Numbers demonstrated the significance of childhood as a subject of interest, and children as an audience, throughout the 1910s and 1920s. In his first Children’s Number editorial, Du Bois articulated what would become the dominant construction of childhood within the pages of the Crisis: "Your child is wiser than you think" ("Of Children" 288). For Du Bois in the pages of the Children’s Number, children as an audience were sophisticated, intelligent, and capable, able to move seamlessly between descriptions of NAACP civil rights efforts and fanciful poetry, between blunt assessments of brutal racial prejudice and studio photographs of upper class children. The "wise" child of Du Bois’s Crisis was also resolutely political, ready to take action towards the cause of civil rights. Although Du Bois did not encourage discussions of racism too early in a child’s life (explaining, "It is wrong to introduce the child to race consciousness prematurely" ("Of Children" 288)), the real threat to black childhood was total parental protection, as Du Bois argues his first Children’s Number editorial: "Once the colored child understands the world’s attitude and the shameful wrong of it, you have furnished it with a great life motive — a power and impulse toward good, which is the mightiest thing man has" (289). When children recognize prejudice, they should be trained for the battle that awaits them, Du Bois argues. The pages of the "Children’s Number" thus served as sustenance for children as race leaders, offering them information about injustices as well as creative writing that often bolstered the child’s racial self image [note].

The idea for a separate children’s magazine first surfaces in an NAACP column by Carrie W. Clifford, titled "Our Children," in the 1917 Children’s Number. Here Clifford outlines the activities of the "Juvenile Department" of the organization, which includes readings of Shakespeare by black performers, presentations of creative writing by young people, staging of two plays ("Fulfillment" by Hallie E. Queen and the unattributed "Tradition"), a field trip to Frederick Douglass’s home, and a tribute to Archibald H. Grimké; all of these activities suggest a robust creative energy among child NAACP members and supporters of the Crisis magazine. Clifford ends by asking, "Dare we report to you briefly of our dreams?" (306), and continues with a description that would seem prescient:

A children’s magazine, where juveniles may send stories, drawings, charades, puzzles, etc., and to which grown-ups may also contribute whatever will help us reach the goal of race unity. The life story of the colored American is truly so marvelous that it can be woven into stories more fascinating and entertaining than any fairy-tale it has ever entered into the mind of man to conceive. . . .

Another idea is to gather and preserve the folk-tales of the race. A number of games have been prepared which are designed to bring to the juveniles the wealth of information concerning the race, and in a most entertaining form. It is through story-telling, games, recitations and periodicals that we hope to awaken in the children race consciousness and race pride. (306-307)

Clifford’s description of the young NAACP members’ "dreams" conspicuously anticipates the contents of Du Bois’s children’s magazine. Truly an inclusive assemblage, The Brownies’ Book published biographies, games, puzzles, quizzes, poetry, plays, folk tales, and short stories, both by adults and by young people. Remembering Clifford’s call for a children’s periodical permits us to understand the multiple threads that led to the initiation of The Brownies’ Book. Du Bois’s biographer, David Levering Lewis, sees the children’s magazine as an extension of Du Bois’s own activities as a parent; he explains that the time Du Bois’s daughter, Yolande, had spent in a British boarding school was destructive to her sense of racial pride, and that the magazine became a way for Du Bois to make amends: "her father may well have felt that his children’s magazine afforded another opportunity for parental advice — advice that now had the painful, chastening, compensatory benefit of hindsight" (32). Another factor that locates the origins of The Brownies’ Book in Du Bois’s role as a parent of Yolande is the September 1912 announcement of next month’s Children’s Number, in which Yolande requests creative writing: "Little Girl looked up from her stewed beans: ‘Will it have a children’s story?’ she asked. The Editor looked down at her. ‘Really, I hadn’t planned--’ ‘But who ever heard of a Children’s Number without a story for children?’ persisted Little Girl. ‘Why—to be sure,’ surrendered the Edtior. So the Children’s Number in October will have a children’s story to go with the baby faces" ("Publisher’s Chat" 251). But in addition to his particular position as a father, Du Bois must have listened to the voice of Clifford, who spoke for a body of creative and politically active "juvenile" NAACP members. Recalling Clifford enables us to recognize the involvement and influence of children during the Harlem Renaissance, as well as to consider Du Bois’s receptivity to their request for a creative outlet that would spur racial self-respect.

The final factor propelling the emergence of The Brownies’

Book was the surge in racial violence in 1919 (the year that prefaced

the magazine’s appearance). Although his editorials in the Crisis repeatedly argue against sheltering children from social

realities, Du Bois certainly recognized the severity of the information offered

to children in the October issues. He explains in an October 1919 editorial,

titled, "The True Brownies," "To the consternation of the Editors of The Crisis

we have had to record some horror in nearly every Children’s Number — in 1915,

it was Leo Frank; in 1916, the lynching at Gainseville, Fla.; in 1917 and 1918,

the riot and court marital at Houston, Tex., etc." (285). The "Red Summer" of

1919 brought intensified white racial viciousness nationwide. Angered by African

American resistance to discriminatory labor and housing practices, white mobs

rioted in Chicago, Washington, D.C., Elaine, Arkansas, and at least twenty other

towns and cities, killing hundreds of African Americans. Du Bois found it

difficult to balance the needs of his "wise child" in the face of such

brutality, asking of his obligation to cover race riots, "what effect must it

have on our children? To educate them in human hatred is more disastrous to them

than to the hated; to seek to raise them in ignorance of their racial identity

and peculiar situation is inadvisable — impossible" ("True Brownies" 285).

Despite the note of caution in his editorial, Du Bois did not retreat from

connecting children to political action. Even within this 1919 Children’s

Number, Walter White’s scathing article on the Chicago riots, "Chicago and Its

Eight Reasons," is headed by an image of a line of screaming babies; the babies

are followed on the next page by a photograph of an unnamed murdered African

American man (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4, Crisis, Oct. 1919.

Figure 4, Crisis, Oct. 1919.

Figure 5, Crisis, Oct. 1919.

The next issue also excerpts Claude McKay’s

militant poem "If We Must Die" and pairs it with a photograph of a somber, nude,

vulnerable female toddler (Figure 6).

Figure 5, Crisis, Oct. 1919.

The next issue also excerpts Claude McKay’s

militant poem "If We Must Die" and pairs it with a photograph of a somber, nude,

vulnerable female toddler (Figure 6).

Figure 6, Crisis, Nov. 1919.

How did young people respond to the

provocative combination of lynching reports with images of children? Did they

recognize Du Bois’s call to take up the battle against racial prejudice? In

truth, only a few records of the effects of Crisis

Children’s Numbers remain. One, by Horace Mann Bond, the first black president

of Lincoln University, appears in a tribute to Du Bois after his death, and

speaks of the influence of the Children’s Numbers on Bond’s rural Kentucky

childhood [note]:

Figure 6, Crisis, Nov. 1919.

How did young people respond to the

provocative combination of lynching reports with images of children? Did they

recognize Du Bois’s call to take up the battle against racial prejudice? In

truth, only a few records of the effects of Crisis

Children’s Numbers remain. One, by Horace Mann Bond, the first black president

of Lincoln University, appears in a tribute to Du Bois after his death, and

speaks of the influence of the Children’s Numbers on Bond’s rural Kentucky

childhood [note]:

It is difficult to underestimate the influence of the Crisis’s Children’s Numbers on an audience of young people like Bond, whose 1940s social science research on black childhood would sustain the NAACP’s work on behalf of Brown v. Board of Education, and who would become the father of Julian Bond, a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The effects of the Children’s Number can only be surmised through such anecdotal evidence, but one can sense in Bond’s testimony the generative effects of Du Bois’s willingness to tell the truth about both prejudice and the dignity of blackness.

For Du Bois, The Brownies’ Book was a way to balance exposure to social realities with nurturing a child’s sense of well being, pride, and optimism. This separate magazine for young people aimed to "seek to teach Universal Love and Brotherhood for all little folk — black and brown and yellow and white" ("True Brownies" 286). Du Bois lists seven particular goals for the magazine [note], including "To make colored children realize that being ‘colored’ is a normal, beautiful thing" (286). Many of the Harlem Renaissance’s most famous writers saw their first publication within The Brownies’ Book, as did a teenaged Langston Hughes, whose poetry, travel writing, games, and drama often drew on his experience visiting his father in Mexico. Other important Harlem Renaissance writers were included in the periodical, such as Georgia Douglas Johnson, Nella Larsen, James Weldon Johnson, Arthur Huff Fauset, and Mary Effie Lee (maiden name of Effie Lee Newsome). Undoubtedly, however, the most influential force alongside Du Bois in shaping The Brownies’ Book was Jessie Fauset, the literary editor of the Crisis magazine from 1919 to 1926 as well as literary editor of the children’s magazine; in addition to many attributed poems and stories within the children’s magazine, Fauset also authored much of the magazine’s unattributed or anonymous material. Fauset wrote a monthly feature titled "The Judge," in which four children and an elderly Judge discuss questions about education, child behavior, and social practice. Dianne Johnson-Feelings writes of the inclusion of children in determining corrective social action, "This Judge does not solely lay down the law; he also acknowledges that the Law is in need of profound revision. And the Judge makes it clear that children will be a part of this process of civic activity and legal change" (339). In Fauset’s column, children were imagined as thoughtful, inquisitive, engaged citizens. They also were deeply committed to education and to race improvement. For instance, in the October 1921 "The Judge" column, the four children correct each other’s grammar and pledge to attend school faithfully; one boy proclaims after listening to the conversation, "from now on, I’m going to pay attention to my lessons and be a cultured boy too!" (294).

With a magazine of such range, the perspective on race relations and on the role of childhood to racial progress is not monolithic; some pieces seem to encourage a retreat into fairy land as a way to escape from racial tensions, while others use biography of famous African Americans — like Harriet Tubman, Crispus Attucks, Paul Cuffee, and others — as models to inspire activism in child readers. Perhaps its most overtly political feature comes directly from Du Bois in a monthly column he wrote for the magazine: "As the Crow Flies" offers sophisticated reportage of social and political event from across the globe. Du Bois, who wrote the column, presents complicated and timely commentary on national and international politics, with an anti-imperialist, internationalist sensibility. In other sections of the journal, The Brownies’ Book takes an intimate stance on South Africa, offering the story of Olive Plaajte, a young girl who died of rheumatic fever after being exposed to the elements in a segregated train station (Dec. 1921). As critic Sharon Harris argues about recovery of neglected literary texts, "the scope of contexts in which we place texts is really what recovery is about, and in that sense our work has and always will have only begun" (295). The international perspective of The Brownies’ Book asks us to reconsider the nationalist narratives through which black children’s literature has been read (largely as building race pride at home and concretizing aesthetic traditions that spring from an American context, like folk stories, for example). In fact, "As the Crow Flies" and other material in the magazine could be read through the "transnational turn," as Shelly Fisher Fishkin described it in her 2004 American Studies Association address, so important to current scholarship in American literature. From its inception, black children’s literature has had an internationalist sensibility.

It is in "As the Crow Flies" that Du Bois turns directly to racial violence, for

within the first issue of The Brownies’ Book, Du Bois

includes a straightforward description of the Red Summer: "There have been many

race riots and lynchings during the year. The chief riots were in Washington,

Chicago, Omaha; Longview, Texas, and Phillips County, Arkansas" ("As the Crow

Flies" 24). Du Bois does not tell the reader how to respond, nor does he attach

the description to photographs of murdered individuals, as he had in the 1919

Children’s Number. Instead, Du Bois includes in this first issue (Jan. 1920) an

image of children marching in the 1917 Silent Protest Parade [note], a demonstration organized by the

NAACP in response to the July 2nd East St. Louis riot, and to lynching in

general (Figure 7).

Figure 7, The Brownies’ Book, Jan. 1920. Image of the “Silent Protest Parade of 1917.”.

The children in the image hold signs saying "Give Us a

Chance to Live," "Thou Shalt Not Kill," and "Mother, Do Lynchers Go To Heaven?"

Protest, then, is the proper response to injustice according to Du Bois, for

children should be involved in politics and in the larger work of the civil

rights organization. The detailed political information offered by "As the Crow

Flies" confirms that the magazine expected children to be concerned with

injustice at home and across the globe, and that information would fuel social

action [note]. The call to child activism is certainly at play in the

pages of the magazine, and Du Bois’s groundbreaking construction of the "wise

child" informs much of its political writing. As Horace Mann Bond reminds us, Du

Bois valued children enough to share the "real truth about a brutal social

order" (16) in the hopes of involving youth in social activism.

Figure 7, The Brownies’ Book, Jan. 1920. Image of the “Silent Protest Parade of 1917.”.

The children in the image hold signs saying "Give Us a

Chance to Live," "Thou Shalt Not Kill," and "Mother, Do Lynchers Go To Heaven?"

Protest, then, is the proper response to injustice according to Du Bois, for

children should be involved in politics and in the larger work of the civil

rights organization. The detailed political information offered by "As the Crow

Flies" confirms that the magazine expected children to be concerned with

injustice at home and across the globe, and that information would fuel social

action [note]. The call to child activism is certainly at play in the

pages of the magazine, and Du Bois’s groundbreaking construction of the "wise

child" informs much of its political writing. As Horace Mann Bond reminds us, Du

Bois valued children enough to share the "real truth about a brutal social

order" (16) in the hopes of involving youth in social activism.

In another fundamentally respectful move, Du Bois gave over much of the space of the magazine to young writers. Just as the editor aimed for child participation in civil rights efforts, he and Jessie Fauset welcomed the creative involvement of readers in the magazine. Pocahontas Foster, a frequent contributor, began by writing letters to the magazine, and then contributed several stories and poems. John Bolden, a young man figured in a photograph, published "The Three Golden Hairs of the Sun-King" (Sept. 1920) and even Du Bois’s daughter, Nina Yolande Du Bois, wrote creative pieces like "The Land Behind the Sun" (Dec. 1921), nonfiction like "Retrospection" (Aug. 1921), and illustrated others’ work, like Augusta Bird’s story "Hilda and Frederick" (Aug. 1921). Seventeen-year-old Ruth Marie Thomas and her sister interviewed the actor Charles S. Gilpin, and their account of the exchange appeared in the July 1921 issue. As Thomas glowingly describes Gilpin’s approachability, we become aware of the young interviewer’s alertness to how she is treated by adults:

The creative control afforded to readers was quite extraordinary, and one can sense in the example of Ruth Marie Thomas an excitement not only about meeting and interviewing a famous actor, but also about his respectful treatment of young people; and, of course, Thomas is elated to have that conversation published in a national magazine. The magazine also covered readers as news items in its "Little People of the Month" column, which included photographs as well as descriptions of young people and their accomplishments, particularly in terms of education. The sense of pride the magazine inculcated in its readers derived not only from reading the rich biographical essays of historical figures like Phillis Wheatley and Benjamin Banneker, but also from awareness of the experience of its own readers. Typical is the glowing announcement of Mildred Turner’s accomplishment in the September 1921 "Little People of the Month" column: selected to write the "ode" for her high school in Brockton, Massachusetts, Turner achieves "a signal honor for her race, since she is the first Negro to win this distinction at the school" (266). Not only could black children emulate success stories from history, but in their own everyday actions they become the modern heroes of the race. Study of The Brownies’ Book as a periodical and as a site of recovery permits us not only to unsettle canonical notions of children’s literature but also to understand better the way culture operated for black readers in the early twentieth century: periodicals enabled a space for disenfrancized voices to shape expressions of identity and activism, and (to use Jean Marie Lutes) "they created new possibilities for subjectivity and self-display" (337). Lutes continues, "As scholars confront the implications of the interactive modes of reading associated with periodical studies, they are reshaping our understanding of the public — mass politics, public spheres, and public identities" (345). By attending to The Brownies’ Book, we can also reconsider the role of childhood to the public sphere. Listening to the young voices published in the journal permits us to become more attuned to the sense of community sustaining publication efforts and black mass culture, a move that might dislodge attention from the "big names" like Hughes, Du Bois, and Fauset, and permit an assessment of the forces shaping the black public sphere at this moment, for certainly there were more African American readers of periodicals than of books. Lutes argues that "Precisely because writing published in periodicals lacks the prestige and status of the bound book, it is an essential source for scholars who seek insight into writers who — by virtue of their gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, or other factors — have lacked access to the most privileged venues of American letters" (336). We might add age to her list. Attending to the child contributors also allows us to consider the way in which community points both outward towards public articulations and inward towards intimacy of exchange: one can imagine a middle-class black family reading The Brownies’ Book, and the possibilities for the interior life of a child artist who has discovered, finally, a venue for her illustrations, poetry, and ideas.

There are some difficult moments in the magazine for a modern reader. While the

Brownies’ Book does not speak explicitly about

colorism (the tendency to value people with lighter-toned skin over those with

darker skin) many of the children it pictured in studio photographs came from

the black elite, and it also published several times an advertisement (Figure

8) from Madame C.J. Walker, the millionaire beautician, that promises those

"unfortunate ones whom nature had not given long, wavy hair and a smooth, lovely

complexion" new hope through bleaching creams.

Figure 8, The Brownies’ Book, Nov. 1921.

Then again, the magazine also

offered celebratory images of children with darker skin, as in this page titled

"Our Little Friends" (Figure 9) from February 1921.

Figure 8, The Brownies’ Book, Nov. 1921.

Then again, the magazine also

offered celebratory images of children with darker skin, as in this page titled

"Our Little Friends" (Figure 9) from February 1921.

Figure 9, The Brownies’ Book, Feb. 1921.

The magazine also

reinterpreted and reclaimed darker children who had public success. One potent

example is popular affection for the child actor Frederick Ernest Morrison, who

went by "Little Black Sambo" and "Sunshine Sammy" and co-starred in several

feature films and in "Our Gang" movies. A February 1921 article on the actor

mentions Morrison’s economic success by asserting that, "Ernie is said to

receive enough salary to own a fine home, several automobiles, and dogs and

other pets, just like other movie stars" ("Little People" 60); it also

politicizes Morrison’s ability to charm an audience with humor: "In Los Angeles,

little Ernie is spoken of as a ‘race benefactor’, since each day he makes

thousands of people laugh and forget their troubles" ("Little People" 61)

(Figure 10).

Figure 9, The Brownies’ Book, Feb. 1921.

The magazine also

reinterpreted and reclaimed darker children who had public success. One potent

example is popular affection for the child actor Frederick Ernest Morrison, who

went by "Little Black Sambo" and "Sunshine Sammy" and co-starred in several

feature films and in "Our Gang" movies. A February 1921 article on the actor

mentions Morrison’s economic success by asserting that, "Ernie is said to

receive enough salary to own a fine home, several automobiles, and dogs and

other pets, just like other movie stars" ("Little People" 60); it also

politicizes Morrison’s ability to charm an audience with humor: "In Los Angeles,

little Ernie is spoken of as a ‘race benefactor’, since each day he makes

thousands of people laugh and forget their troubles" ("Little People" 61)

(Figure 10).

Figure 10, The Brownies’ Book, Feb. 1921.

Skirting the fact that Morrison earned his success by sometimes

playing a picaninny figure, Du Bois’s and Fauset’s publication emphasizes

instead his success in a white world, a trait that might align him with the

trickster tradition. The magazine was certainly not unaware of popular

assumptions about black children. While it may have issued advertisements for

skin bleachers, at the same time its editorial content recuperated images of

dark skinned children, and transformed an actor who sometimes enacted the

pickaninny figure into a capitalist success story.

Figure 10, The Brownies’ Book, Feb. 1921.

Skirting the fact that Morrison earned his success by sometimes

playing a picaninny figure, Du Bois’s and Fauset’s publication emphasizes

instead his success in a white world, a trait that might align him with the

trickster tradition. The magazine was certainly not unaware of popular

assumptions about black children. While it may have issued advertisements for

skin bleachers, at the same time its editorial content recuperated images of

dark skinned children, and transformed an actor who sometimes enacted the

pickaninny figure into a capitalist success story.

An impressive variety of material was available to the child turning the pages of The Brownies’ Book: fairy tales, African folktales, Brer Rabbit stories, and whimsical poetry all sit side-by-side, a testament to the generous and capacious aesthetic of Jessie Fauset. The multiple genres [note] represented in the magazine speak to Du Bois’s and Fauset’s awareness of the various literary and social worlds inhabited by black children. Conversant in fairy tale and in oral tradition, in poetic modes and in anthropological narrative, the child reader was imagined as moving seamlessly between genres. Although the Crisis reached peak circulation of 100,000 in the late teens, support for the children’s magazine was not as robust (at approximately 5,000 subscriptions); as a result, the periodical concluded publication after two years.

The tendrils of The Brownies’ Book extended throughout the remainder of the Harlem Renaissance. Du Bois continued the Children’s Number of the Crisis, and from 1925 to 1930 published Effie Lee Newsome’s "Little Page" — a collection of nature writing and poetry for young people — nearly every month. The Brownies’ Book had a particularly formative effect on Langston Hughes, as it was the site of his first national publications. He would publish poetry for young people and adults throughout the 1920s, collecting much of it in his collection for children, The Dream Keeper (1932). In fact, Hughes remained committed to a young audience throughout his long literary career. With his friend Arna Bontemps, Hughes wrote fiction like Popo and Fifina: A Story of Haiti (1932) and The Pasteboard Bandit (written 1935/published 1997), as well as nonfiction for a young audience, including the First Book of Negroes (1952), First Book of Jazz (1955), First Book of Rhythms (1954), Famous Negro Music Makers (1955), and the popular photographic picture book A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956), among others. Bontemps himself, in large part through the influence of Hughes as a children’s author, had a long and productive career in children’s literature, publishing more than a dozen books for young people from 1932 to 1972.

The Brownies’ Book also jump-started the career of dramatists like Willis Richardson, who would become the first black playwright to stage a serious play on Broadway, "The Chip Woman’s Fortune" (1923). Richardson got his start publishing children’s plays in The Brownies’ Book, including "The King’s Dilemma" (Dec. 1920), "The Children’s Treasure" (June 1921) and "The Dragon’s Tooth" (Oct. 1921). He would become the first black playwright to issue a volume of his own children’s plays, The King’s Dilemma and Other Plays for Children: Episodes of Hope and Dream (1956), as well as editing two significant collections of plays for young people by African Americans in the early 1930s, Plays and Pageants from the Life of the Negro (1930) and (with May Miller) Negro History in Thirteen Plays (1935). After Du Bois left the Crisis editorship, Effie Lee Newsome — the Crisis "Little Page" writer who began by publishing poems and stories in The Brownies’ Book — would publish a volume of poetry for children, Gladiola Garden (1940), gorgeously illustrated by the "grande dame" of African American painting, Lois Mailou Jones. The Brownies’ Book also offered space to young female artists like Laura Wheeler (Waring), who would become a major portraitist of the Harlem Renaissance, as well as Crisis illustrator Hilda Wilkinson, who with Wheeler would illustrate children’s texts like Elizabeth Ross Haynes’s Unsung Heroes (1921).

As a magazine that addressed the social and political investments of black childhood, The Brownies’ Book was truly groundbreaking. More to the point, it was the first magazine to take black children seriously, to tell them the truth about racial prejudice and cultural distinctiveness. The multiplicity of material offered to a young audience served the variety of experiences and needs of its readers. But no matter whether the magazine offered a folk story or a fairy tale, it always put first the goal of cultivating racial pride through knowledge of African American perspective and accomplishments. Jessie Fauset in particular recognized children’s desire for a magazine that addressed their experience and potential. In the magazine’s January 1920 inaugural poem, "Dedication," Fauset writes:

For Fauset and Du Bois, the magazine offered young people a stable source of information about the race’s history, and a venue for children to explore their own artistic and political interests. It is quite telling that Du Bois and Fauset title the magazine The Brownies’ Book rather than The Brownies’ "magazine" or "monthly": the editors sought the stability, authority, and permanence of print for this journal of black childhood. While its span of publication was relatively brief, the accomplishment of The Brownies’ Book lives on. We witness its success in the careers of major writers like Hughes, and in the continued presence in children’s literature of its pioneering aesthetic. The black cultural pride we discover within The Brownies’ Book courses through the wide-ranging work of African American children’s writers today.

Works Cited

- Bond, Horace Mann. "The Legacy of W. E. B. Du Bois." Freedomways (Winter 1965): 16-17.

- Clifford, Carrie W. "Our Children." Crisis 14.6 (Oct. 1917): 306-07.

- Danky, James Philip. African-American Newspapers and Periodicals: A National Bibliography. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1998.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. "As the Crow Flies." The Brownies’ Book 1.1 (Jan. 1920): 23-25.

- —. "Crisis Children." Crisis 32.6 (Oct. 1926): 283.

- —. "Discipline." Crisis 12.6 (1916): 269-70.

- —. "Of Children" Crisis 4.6 (Oct. 1912): 287-89.

- —. "Publisher’s Chat." Crisis 4.5 (Sept. 1912): 251.

- —. The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1903.

- —. "The True Brownies." Crisis 18.6 (Oct. 1919): 285-86.

- English, Daylanne. Unnatural Selections: Eugenics in American Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2004.

- Fauset, Jessie. "Dedication." The Brownies’ Book. 1.1 (Jan. 1920): 32.

- —. "The Judge." The Brownies’ Book. (Oct. 1921): 294.

- Gaines, Kevin K. Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1996.

- Harris, Sharon. "‘Across the Gulf’: Working in the ‘Post-Recovery’ Era." Legacy 26.2 (2009): 284-98.

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. "Hope." Crisis 14.6 (Oct. 1917): 293.

- Johnson-Feelings, Dianne. "Afterword." The Best of The Brownies’ Book. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. 335-346.

- Lewis, David Levering. W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963. New York: Henry Holt, 2000.

- "Little People of the Month." The Brownies’ Book. Feb. 1921: 60-61.

- "Little People of the Month." The Brownies’ Book. Sept. 1921: 288-90.

- Lutes, Jean Marie. "Beyond the Bounds of the Book: Periodical Studies and Women Writers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries." Legacy 27.2 (2010): 336-56.

- Mitchell, Michelle. Righteous Propagation: African Americans and the Politics of Racial Destiny after Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2004.

- Smith, Katharine Capshaw. Children’s Literature of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2004.

- —. "Childhood, the Body, and Race Performance: Early 20th-Century Etiquette Books for Black Children." African American Review 40.4 (1996): 795-811.

- Thomas, Ruth Marie. "An Interview With Charles S. Gilpin." The Brownies’ Book 2.7 (July 1921): 211-12.