har1899.2007.001.001.jpg

har1899.2007.001.005.jpg

Books by Joel Chandler Harris.

LITTLE MR. THIMBLEFINGER AND HIS

QUEER COUNTRY. Illustrated by OLIVER

HERFORD. Square 8vo,

$2.00.

MR. RABBIT AT HOME. A Sequel to Little

Mr. Thimblefinger and His Queer Country.

Illustrated by OLIVER HERFORD . Square 8vo,

$2.00.

THE STORY OF AARON (SO-NAMED) THE

SON OF BEN ALI. Told by his Friends and

Acquaintances. Illustrated by OLIVER Herford .

Square 8vo, $2.00

AARON IN THE WILDWOODS. Illustrated by

OLIVER HERFORD . Square 8vo, $2.00.

PLANTATION PAGEANTS. Illustrated by E.

BOYD SMITH . Square 8vo, $2.00.

NIGHTS WITH UNCLE REMUS. Illustrated.

12mo, $1.50; paper, 50 cents.

UNCLE REMUS AND HIS FRIENDS. Illustrated .

12mo, $1.50.

MINGO, AND OTHER SKETCHES IN BLACK

AND WHITE. 16mo, $1.25; paper, 50 cents.

BALAAM AND HIS MASTER, AND OTHER

SKETCHES. 16mo, $1.25.

SISTER JANE, HER FRIENDS AND ACQUAINTANCES .

A Narrative of Certain Events and

Episodes transcribed from the

Papers of the late William Wornum. Crown

8vo, $1.50.

TALES OF THE HOME FOLKS IN PEACE

AND WAR. Illustrated. Crown 8vo, $1.50.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

BOSTON AND NEW YORK .

har1899.2007.001.006.jpg

"BRER RABBIT ... SOT UP AN' LAUGH" (page 243)

har1899.2007.001.006.jpg

Plantation Pageants

BY

JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS

AUTHOR OF "UNCLE REMUS,"

ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

E. BOYD SMITH

[illustration -

]

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1899

har1899.2007.001.007.jpg

COPYRIGHT, 1899

BY JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS AND HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN &

CO.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

har1899.2007.001.007.jpg

har1899.2007.001.008.jpg

har1899.2007.001.008.jpg

har1899.2007.001.009.jpg

PLANTATION PAGEANTS

I.

AFTER THE WAR.

General Sherman had done the

best he could for the Abercrombie place. He had waved his hand, and grim War shrunk

away out of sight; he had given a signal, and all the mules and horses and live stock

that had been taken away by the foragers were returned in a jiffy; he had lifted his

finger, and a cordon of soldiers was placed around the house and the outlying

buildings. Everything was in its place; so far as the eye could see, war had forcibly

taken no tolls from the plantation.

Nevertheless, when, on a misty morning in November , the Federal commander bade the

place good-by, and pushed his army southward along the Milledgeville road, he left

the plantation in

har1899.2007.001.010.jpg

very bad shape, so far as Buster John and Sweetest Susan were concerned. Something

was wanting — the place was n't the same. The silence that fell upon everything, when

the army clink-clanked out of hearing, was something terrible. The horses and mules

stood under the big shed and shivered dumbly; and the cattle huddled together on the

western side of the gin-house, for the wind was from the east, and blowing with a

penetrating moisture that was more than cold.

There was no gossip among these animals that people think are dumb. They had been

badly frightened by the hurly-burly that beset them; they might talk about it after a

while when the sun shone out, or when the grass came; but meantime the east wind was

blowing, and no matter how intelligent an animal may be, he can never tell what that

wind will bring when it has begun to blow. Now the grass-eating animals know very

well when a storm is coming. The flesh-eaters merely grow frisky and have a frolic;

but the grass-eaters make for shelter, and if they have a home to go to, they go

there; but the east wind — well, that is their problem, as it was Aaron's, only the

son of Ben Ali never allowed it

har1899.2007.001.010.jpg

to blow on the back of his neck; so

that when other people were going about complaining of rheumatism or neuralgia, or

were in bed with pleurisy or pneumonia, the son of Ben Ali was usually on his feet

and in fairly good health.

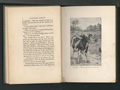

Well, on this remarkable day, the animals in the horse-lot and in the pasture were

quiet and morose. They had been shaken up in the first place with their strange

experiences, having been driven helter-skelter two or three miles from home in the

wind and mist, and helter-skelter back again, with drums beating and bugles blowing,

and nobody to explain it all. Old June, the milch cow, thought she had lost her calf,

but after a while she felt it running along by her side, and it was standing under

her now, a shivering , shaky, shaggy thing that looked more like a ba-ba-black-sheep

than a respectable calf.

Anyhow, they all stood on the sheltered side of the gin-house, and were very quiet,

as the steam rose from their backs and the fog issued from their nostrils. They were

not in a playful mood, and there was nothing about them to interest Buster John and

Sweetest Susan, when later in the day these young adventurers paid them a visit

har1899.2007.001.011.jpg

of inspection. Old June moaned at them in a familiar way, but that was all the

welcome they received.

"I don't believe they've been fed," said Sweetest Susan with a sigh.

"Why, of course not," exclaimed Buster John; "Aaron can't do everything."

"Where are Simon and Johnny Bapter and the rest?" the little girl asked.

Sure enough, where were they? Where were all the men and women, and the boys and

girls, who used to make the negro quarters gay with laughter? Where was old Fountain?

Yes, and where was Drusilla? This was the kind of day when there should be a fire

blazing on the hearth of every cabin, if only to keep out the dampness; but smoke was

coming out of only one chimney, and even that was not a free and friendly smoke. It

was a thin, wavering ribbon of blue, hardly visible until the wind seized it and tore

it to tatters.

"I don't know what you are going to do," said Sweetest Susan, "but I am going to find

Drusilla. I have n't seen her since last night."

Sweetest Susan went toward the negro quarters, followed by Buster John, and as they

went along

har1899.2007.001.011.jpg

[illustration - OLD JUNE ... THOUGHT SHE HAD LOST HER CALF ]

har1899.2007.001.012.jpg

har1899.2007.001.012.jpg

they were even more and more impressed

with the silence that had fallen over everything. On all rainy days, except this

particular day, so far as they could remember, they could n't go within a quarter of

a mile of the quarters without hearing singing and loud laughter, or the sound of

negroes scuffling and wrestling. But now the whole place seemed to be deserted. Big

Sal's cabin was the first they came to. The door was open, and they entered. For a

moment the interior was so dark that they saw nothing, but presently they could see

Big Sal sitting on the floor, carding out her gray hair. Usually she wore it in

wraps, but they were now untwisted, and, as she carded them out, they stood at right

angles to her head, and gave her a very wild and ferocious appearance.

She neither turned nor paused in the carding when the children stepped somewhat

timidly in the door. People said she was sullen; but she was very sensitive and

tender-hearted, and always famishing for some one to love. The negroes thought she

was both cruel and suspicious, and Buster John and Sweetest Susan were somewhat

doubtful about her. For a woman of sixty years, who had known hard work, and trouble

with it, she was well preserved.

har1899.2007.001.013.jpg

"Aunt Big Sal," said Sweetest Susan, "where is everybody?"

"Gone, honey, de Lord knows whar; gone, honey, de Lord knows how."

She turned as she spoke, and her hair bristling out gave her countenance such a wild

aspect that the children involuntarily shrank back. They had never seen her with her

hair down before.

She raised her hands. "Be afeard er any an' ev'ybody, honey, but don't be afeard er

me! Dodge frum one an' all, but don't dodge frum me. Not frum me! No, my Lord!"

"Are they all gone?" asked Buster John.

"Mighty nigh all, honey; mighty nigh all un um. Dem what went wuz big fools, an' dem

what stayed may be bigger ones, fer all I know. I 'd 'a' been gone myse'f, but I went

'roun' yander in de grave-yard, whar dey put dat cripple chile, an' sump'in helt me.

I could n't go 'way an' leave 'im." She was speaking of Little Crotchett, who had

been dead and buried these many long years.

"Why did they go?" inquired Sweetest Susan.

"Huntin' freedom," responded Big Sal. "Yes, Lord, huntin' freedom! I hope dey 'll

fin' it; dat I does."

har1899.2007.001.013.jpg

"Grandfather says all the negroes are free now," said Sweetest Susan.

"Did he say dat? Did he say dat wid his own mouf? Well, I thank my stars! I'm free,

den! Me an' all de balance!"

"So Grandfather says," remarked Buster John.

"Well," said Big Sal, "ef I'm free, I better get up frum here an' go ter work. What

does Marster want us ter do? I'm gwine up dar an' ax 'im."

The children went to the other cabins and found them empty, but in Jemimy's house

they found Drusilla crying. You may imagine Sweetest Susan's grief when she made this

discovery. Drusilla was ready with her tale of woe.

"Mammy walloped me kaze I won 't go off wid de balance un um," sobbed Drusilla. "She

say ef I stay here she got ter stay. I tell her I'll do anything but dat; I'll tell

lies, I'll steal, but I won 't go off frum here; dey got to kill me dead an' tote me.

An' den mammy walloped me."

"You need n't ter b'lieve a word er dat!" cried Jemimy, who came in at that moment.

"I tol' dat gal it would be better for we all ter go ef we wanter be free sho 'nuff,

an' wid dat she

har1899.2007.001.014.jpg

fell on de flo' and 'gun to waller an' holler, tell I 'bleege to paddle 'er. I don't

wanter go no wuss 'n she do, but dey say dat if we don't go 'way from whar we b'long

at, we never is ter be free. Dat what de niggers on de nex' plantation say. I wuz

born here, an' ef dis ain't my home, I dunner whar in de roun' worl' I got any."

There was a break in Jemimy's voice as she said this. Buster John paid no attention

to it; but Sweetest Susan went close to her and leaned against her, and the negro

woman put an arm around the child. It was as if a tramp steamer had thrown out an

anchor within sight of the lights of home.

"Who cooked breakfast this morning?" asked Sweetest Susan.

"Me," replied Jemimy. "I know'd somebody had ter cook."

"I thought so," said the child. "The biscuits were mighty good."

It was some time before Jemimy said anything. She rose and pushed the child from her,

remarking : "I dunner what come over me, but ef I set here wid my arm 'roun' you, an'

you talkin' dat away, I'll be boo-hooin' 'fo' I know myse'f. Git up frum dar,

Drusilla, 'fo' I break yo' neck!"

har1899.2007.001.014.jpg

Before Drusilla could make any preparation to rise, there came a loud rap on the

door-facing.

"Nobody but old Fountain," said the newcomer ; "old Fountain, as muddy as a hog, and

harmless as a dove."

Harmless or not, he was certainly muddy. As he came in, the legs of his pantaloons,

rubbing together , sounded as if they were made of leather. His coat was full of red

mud, and mud was on his hat and in his hair.

"Whar is you been?" asked Jemimy.

"Fur enough ter go no furder," responded old Fountain, shaking his head. "I went

a-huntin' freedom. De kin' I foun' will las' me a whet; I promise you dat."

"You don't tell me!" exclaimed Jemimy.

"I does," said Fountain, "an' I could tell yo' lots mo' dan dat ef I had time. Dey

sot me ter work liftin' waggin wheels out er de quagmire, an' den a driver

rap-jacketed me wid his whip — well, you see me here, don't you? An' f we 're bofe

alive, you'll see me here ter-morrow an' de day after."

"An' dey wa'n't no freedom dar?" questioned Jemimy. She spoke under her breath, as if

afraid to hear the answer.

har1899.2007.001.015.jpg

"I won't say dat," replied Fountain. "Fer dem dat like de kin', 'twuz dar. Some

mought like de change, but not me. I bless God fer what I seed, but I seed 'nuff. I

went, an' I come."

"Why n't you stop an' wash de mud off in de branch?" Jemimy asked presently.

"No, not me," Fountain replied, still shaking his head. "Ter stop wuz ter stay. I

know'd dey wuz a branch at home; an' mo' dan dat, a spring. De idee wuz ter hurry

back an' see ef de natchel groun' had been left!"

"I b'lieve you!" sighed Jemimy. "I come mighty nigh gwine myself."

"You 'd 'a' been sorry!" exclaimed Fountain; "you'd 'a' been sorry plum ter yo' dyin'

day. You see me?" Jemimy nodded her head.

"Well, I been dar. I been right wid um. You can't call it freedom atter you wade thoo

dat mud an' water."

Some one else came to the door. "All eyes open!" cried the newcomer. It was the

refrain of hide-and-seek, and the children laughed when they heard it. They knew the

voice of Johnny Bapter. "All eyes open!" he persisted. "I'm It. Ten, ten, double-ten,

forty-five, fifteen! All eyes open?"

har1899.2007.001.015.jpg

With that Johnny Bapter walked in. He was a thin-looking negro, with a long face, and

a mouth that was always laughing. He would have been very tall, but he stooped a

trifle, and there was a limp to his walk. One of his feet dragged slightly, but he

was nimble as a squirrel for all that. His clothes were wet, but not muddy. He hit

his wool hat against the side of the chimney, and it left its damp print. He looked

at the children and pointed to the wet place. "I tuck its dagarrytype," he said.

Johnny Bapter had once lived in town, and his adventures there, as he made them out,

would have filled a book; and, at times, they were interesting.

"I hope you-all been well," said Johnny Bapter ; "I'm sorter middlin' peart

myse'f."

"Whar you been?" asked Jemimy.

"Kinder see-sawin' 'roun', follerin' de ban's, an' keepin' off de boogers."

"You did n't go wid um?"

"No 'm; not me; I seed dey had plenty comp'ny . Mo' dan dat, I seed um hit ol' man

Fountain dar a whack er two, an' I 'lowed dat ez dey done come dis fur an' nobody

ain't hurt um, maybe dey'd git 'long all right. Dey ain't offer

har1899.2007.001.016.jpg

me no money fer ter go 'long and take keer un um. I wuz over dar at de camps las'

night, an' I see niggers fightin' over scraps an' I hear chillun cryin' fer bread

after de lights done put out. So wid me, it wuz Howdy, and good-by, and I wish you

mighty well. What mo' can a nigger do?"

"Dat's so," sighed Jemimy. "Whar de balance er our folks?"

"Oh, dey'll come back in de due time," said Johnny Bapter laughing. "One'll turn back

at one branch, an' one at anudder; an' dem what don't turn back at de branch will sho

turn back at de river. Dey'll all be home 'fo' de week's out."

Buster John and Sweetest Susan listened to all this, but said nothing. Their minds

hardly grasped the problem with which the negroes were wrestling. They were free, if

they went away. Would they be free if they stayed? It was a very serious matter.

"What dey gwine do when dey come back?" Jemimy asked.

"Work," exclaimed Fountain. "Yes, Lord! work frum sun-up ter sun-down."

"An' dey free too?" suggested Jemimy. She wanted to get at the bottom of the

matter.

har1899.2007.001.016.jpg

Johnny Bapter laughed. "Why, in town whar I stayed, de free white folks work harder

dan niggers. De clerks in de sto' come rushin' ter dinner, an' dey 'd fling der hats

on a cheer, snatch a mouffle er vittles, an' rush out wuss'n ef de overseer wuz

hollerin' at um."

"Is dat so?" replied Jemimy.

"Des like I tell you," said Johnny Bapter.

"I've looked at it up an' down," remarked Fountain, "an' it 's dis away — de man what

eats honest bread is got to work. Dat what de Bible say; maybe not in dem words."

"It sho is so," remarked Johnny Bapter laughing . "I'll work all day an' half de

night, but I don' wanter hear no bugles blow."

Just then Big Sal, who had fixed up her hair, and was quite presentable, having put

on her Sunday clothes, came into the cabin and stood over against the fireplace.

"Wuz dey many er we-all wid dem ar white folks?" she asked.

"Well 'um, I should sesso!" exclaimed Fountain ; "too many, lots too many; more dan

day 'll find rashuns fur, ef I ain't mighty much mistaken ."

har1899.2007.001.017.jpg

"What dey all gwine 'long fer?" asked Big Sal.

"Dey er feared ef dey stay at home dey won't be free. Now, how 'bout dat?" suggested

Fountain .

"Why, grandfather says the negroes are free, whether they go or stay," said Buster

John.

"Grandfather says he is mighty glad the black folks across the creek are free."

"Dey been prayin' fer it 'long 'nuff," remarked Big Sal.

"We-all is free 'nuff," said Johnny Bapter, "but who gwine ter feed us?"

"Dat is so; dat is sho one way fer ter look at it," exclaimed Fountain uneasily.

"Well," exclaimed Jemimy, "I know one thing an' dat ain't two; I'd ruther starve

right here, whar I been born at, dan starve way off in de woods whar nobody don't

know me."

A shadow darkened the door, and there stood Aaron, his right hand raised.

"Well, well! What's all this? Everything to do, and nobody to do it!" He whistled low

under his breath. "Horses and mules to feed, hogs to call, sheep to salt, calves to

take away

har1899.2007.001.017.jpg

from the cows. Well, well! I hear

calls for meal, meat, syrup."

"Hit 's a fac'," assented Fountain.

"You hear my min' workin," said Johnny Bapter . "Make me a hoss out'n meal, meat an'

syrup, and I'll eat 'im up 'fo' yo' eyes."

He rose, stretched himself, let one side of his face drop with affected sorrow, while

the other side was laughing, winked at the children, and darted out into the mist and

rain. Presently the children heard him calling, first the hogs, and then the

sheep.

Aaron and Fountain followed more sedately, and in the course of half an hour the

horses and mules could be heard tearing the fodder from the racks and munching the

ears of corn. By dinner time, according to Aaron's report, there was but one hand

missing from the place; and as he had been hired from the Myrick estate, it was not

expected that he would take up his abode on the Abercrombie plantation.

The fact that all the men, women, and children came back after taking a short holiday

would have been somewhat puzzling to the children's father, if he had been at home;

he had imbibed

har1899.2007.001.018.jpg

some of the modern ideas of business. It would cost something to clothe and feed them

during the winter months, and all this would be clear loss, since their labor would

not be profitable until the planting season began. But there was no problem in it for

the White-Haired Master, the children's grandfather. He looked forward to a period of

chaos and confusion, when labor would be hard to secure. Besides, as he said, the

negroes had helped to make the ample supply of provisions with which the smokehouse

was stocked, and they were entitled to a share of it, especially if they were willing

to remain. Moreover, nearly all were born at the place and knew no other home.

And the plantation seemed to be very lucky in all respects. There were twenty bales

of cotton stored under the gin-house shed, and before Christmas day they were sold at

an average of $250 apiece — cotton was high directly after the war. This put $5000 in

greenbacks in the plantation treasury; and in that, as in other things, the

Abercrombie place was more fortunate than any of the other plantations for miles and

miles around.

har1899.2007.001.018.jpg

But Buster John and Sweetest Susan did n't think so. Everybody was so busy — even

Johnny Bapter, who used to laugh and loaf every chance he had — that the children

were driven back upon themselves. They could talk to the animals on the place, but

that sort of thing ceases to be interesting when you have nothing else to do. They

made signals to Mrs. Meadows, and waited patiently about the spring, hoping to catch

a glimpse of Little Mr. Thimblefinger. But all to no purpose. Buster John was

disgusted, and said so; but Sweetest Susan had clearer ideas about the matter.

"What can you expect?" she asked. "If you were Mr. Thimblefinger, what would you have

done when you saw that great crowd of men and wagons, and heard the drums and the

brass horns? Why, you would n't show your head in a year. And as for Mrs. Meadows,

one of the soldiers let his horse drink from the spring. What do you suppose Mrs.

Meadows thought when she saw that kind of a shadow staring at her through the

water?"

"Well, grandfather says war is the worst thing that ever happened in the world," said

Buster John, "and I reckon it is."

har1899.2007.001.019.jpg

II.

A VIST FROM AUNT MINERY ANN.

The cold and gloomy weather brought by the east wind soon

cleared away, and the sun shone out bright and clear, with a warm breeze from the

south, — a breeze that brought out the violets in great profusion. Still, the place

was not the same. The negroes ceased their songs, except Johnny Bapter, and even he

did n't sing as loudly or as constantly as he used to do. And they ceased to wrestle

and play at night. It seemed that they had problems to consider. They were not sure

of their position; they had nobody to advise them. They might have asked advice on

the subject, but freedom appeared to add to their shyness, and they refrained from

asking for any information or advice. Just why this should be so, nobody has ever

discovered to this day. Some of the less fortunate found strangers to advise with

them and to make them promises that were never to be

har1899.2007.001.019.jpg

redeemed; but on the Abercrombie

place the negroes worked in the dark, as the saying is, except for such counsel as

the strong common sense of Aaron was able to give them. They had the idea that,

having been made the object of what seemed to be a special interposition of

Providence, they were to be sustained and maintained in the same way.

This accounted for the fact that the negroes on most of the plantations left home and

flocked to the towns and cities, where they became the charge of the Freedmen's

Bureau, an institution that did a great deal of good, as well as a great deal of

harm: a great deal of good, because in many cases it prevented actual starvation; and

a great deal of harm, because it left the impression on the minds of the negroes that

they were to be supported by the government whether they worked or not.

But the youngsters who read will say, "What of that?" and cry, "Get along with your

pokey old story, if you have any to tell!" And it is good advice, too; but when you

are writing about a certain period, you want to have something more than the local

color; you want to get at the temper ,

har1899.2007.001.020.jpg

the attitude, the disposition of the people you are writing about; so that when the

youngsters of to-day get a little older they will be able to say, "There's a great

deal of foolishness in that old book, and some history, too," as if their youngsters

will care any more for history than they did.

Well, anyhow, the sun was shining brightly and the air was warm. The tools and

instruments of war were following the courses of the streams that plough seaward, and

nature on the Abercrombie place had forgotten all about them. But, let the sun shine

ever so brightly, the children failed to find Mr. Thimblefinger, and no message came

from Mrs. Meadows. They were patient enough, too. Every day, sometimes in the morning

and sometimes in the afternoon, they wandered down to the spring and sat on a dry

Bermuda embankment , where they could watch developments.

It was noticed that Drusilla never joined in the regrets that Buster John and

Sweetest Susan expressed , when day after day passed and no Mr. Thimblefinger

came.

"I don't believe you care whether he comes or not," cried Sweetest Susan.

Drusilla shook her head. "I'd keer mightily

har1899.2007.001.020.jpg

ef he did come," she said frankly. "I

done been down dar long wid 'im once, and goodness knows I don't wanter resk it no

mo'. Hit seem lak a skeery dream den, an' I don't want no sech dream ter come ter me

no mo'. When folks git so dat water won't wet um, dey better be gwine off ter some

yuther country."

"What 's the matter with you?" asked Buster John brusquely.

"You better ax what de matter wid you-all," exclaimed Drusilla. "Dey ain't nothin' 't

all de matter wid me. But I'll say dis, when you-all see dat ar Mr. Fimblethinger —

ever what his name is — you won't see me. Dat 's what! I'll set here wid you twel he

pop outen de water, and den I'll pop 'way fum here. Ef I'm free, dat's whar my

freedom will shine out."

"Well, you went once," remonstrated Sweetest Susan.

"Dat kinder doin's is like chills an' fever; you may have um once, but you don't want

um twice."

"She'll go," said Buster John.

Drusilla laughed. "I sholy will — 'way fum here. I don't see what you-all wanter fool

wid

har1899.2007.001.021.jpg

dat kinder doin's fer. I'd lots druther see you-all jabberin' wid de jay-birds. Dat's

bad nuff, but it's better'n reskin' yo' life down und' dat spring. Kaze when you go

down dar, dey ain't no tellin' ef you gwine ter come back 'live. En spozen 't wuz ter

cave in on you — yo' pa, and yo' ma, and yo' grandpa would be gwine 'roun' here plum

'stracted, an' dey never would see hair ner hide er you while de worl' stan's. Uh-uh!

I been down dar once, and dat uz twice too many. Dat ar Mr. Fimblefinger kin pop up

and pop down, but I ain't gwine ter pop wid 'im, not less 'n I take leave er my

senses."

The children could n't help but laugh at Drusilla's earnestness, and they laughed

with a better heart because they knew that if they should have another opportunity to

visit the country next door to the world, Drusilla would not allow them to go alone.

But the opportunity never came, and they not only ceased to expect it, but presently

fell in with other adventures that were quite as curious and as interesting, all of

which are to be chronicled , however clumsily, in the pages to follow.

Meanwhile, one afternoon when the sun was preparing to go to bed, and when the

children

har1899.2007.001.021.jpg

were still expecting little Mr.

Thimblefinger, they heard a voice calling from the big road, which was not far away

from the spring: —

"Heyo dar, folks! Will yo' dogs bite?" The voice was that of a negro woman. She was

driving a small steer to a wagon, but had left the vehicle on the side of the road

and had come over the stile. She was tall, and appeared to be about forty years old.

She had a countenance that could smile, but its aspect was now serious, and her eye

was bright and keen.

"You-all oughter know me!" she cried, as she came up. "Dat is, ef eve'ything ain't

been run outen yo' heads by de war-hosses and de war-whoopers."

"I know you!" cried Sweetest Susan; "it's Aunt Minervy Ann Perdue."

"De same," assented Aunt Minervy Ann. "An' not de same nuther. Kaze, I tell you,

honies, dey 's a mighty change whar I live at. You ain't seen Mars Tumlin Perdue go

'long by de road, is you? Well, it 's jest like 'im ter be stoppin' some'rs on de

road talkin' politics. I b'lieve dat man ud stop on de road and talk politics ef he

knowed eve'y minit wuz ter be de nex'.

har1899.2007.001.022.jpg

I

hear tell," Aunt Minervy went on, "dat de Yankees sweep over you-all's place an'

never tuck off a blessed thing."

The children confirmed this by saying that the troops not only had not carried

anything off, but had driven two mules into the lot that didn't belong there. "It

would be funny," Buster John said, "if the two mules should turn out to belong to

Major Perdue." Anyhow, some of the negroes had said the mules belonged to the

major.

"You see dat lil steer out dar," exclaimed Aunt Minervy Ann, "'tain't much more dan a

yearlin'; well, dat ar steer is de onliest four-footed creetur dat dey lef' at

Perdue's; an' dey would n't 'a' lef' him ef I had n't a driv' 'im in my house an'

kep' 'im in dar whiles dem people wuz rumagin' 'roun' an' trompin' by. Dey shot de

chickens yit, an' de turkeys, an' even down ter de goslin's; an' dey fair stripped de

smoke-'ouse an' de sto'-room."

"That's mighty funny," remarked Buster John.

"It may seem like hit's funny to you-all, honey," said Aunt Minervy Ann, "but 'tain't

funny up dar whar we-all live at. Dey wouldn't 'a' done so bad ef it had n't 'a' been

fer Mars Tumlin. He went out, he did, time dey come in de yard, an'

har1899.2007.001.022.jpg

he cuss'd um an' sass'd um des ez

long ez dey wuz a'er one un um in sight. I tried to make signs fer ter make 'im hush,

but, shoo! his dander wuz up, and you des ez well make signs at a gate-post. He say

he gwine ter move ter town; an' when I ax 'im what we gwine live on, he 'low dat we

can starve lots better in town dan we kin in de country ; an' I spec' dat 's so, kaze

we won't be so lonesome. Dey ain't a livin' soul on dat place but me and Mars Tumlin,

an' yo' cousin Vallie an' Hamp. All de niggers done gone, kaze when dey come an' ax

Mars Tumlin what dey mus' do, he bein' mad, 'lowed dey could all, go to de ol' Boy,

and be janged. He say he comin' over here fer ter borry sump'n ter eat; and he better

be comin', too, fer de day 'll be gone fo' you know it."

"Yonder he is now," said Sweetest Susan. The children were well acquainted with Major

Perdue. He was not only kin to them in some remote way, but he was very jolly company

when in the humor — and this was pretty much all the time; for although the major had

a temper which he took small pains to control, it was only on rare occasions that he

displayed it. He was in a fine

har1899.2007.001.023.jpg

humor now, for he came forward laughing and gave the children each a hearty

smack.

"Minervy Ann," said the major, "I thought I told you to curry that horse and plait

his mane before you hitched him to the buggy."

"You did tell me dat," replied Minervy Ann; "an' I tol' you dat ef you'd get some hot

water an' soap, an' wash de horn off his haid, I 'd plait bofe mane an' tail."

"I clean forgot it," the major declared. "Well, you stay here and talk to these

chaps, and I'll call on Cousin Abercrombie and see if I can't beg or borrow a few

rations. When I want you I'll call you, and then you can drive your carriage in at

the side gate there."

Aunt Minervy Ann looked after the major and laughed. "I hope ter goodness," she said,

as she sat down by the children — "I hope ter goodness dat he won't say he want de

vittles cooked. Kaze ef he done dat, it 'd put me in min' er dat ol' tale my mammy

useter tell me."

"What tale was that?" Sweetest Susan asked.

"Oh! you-all done hear tell un it mo' times dan your been ter chu'ch. You ain't never

had ol' Remus to tell it ; but dar is dat ol' A'on, an'

har1899.2007.001.023.jpg

ol' Fountain, an' Big Sal — what dey

been doin' all dis time ef dey ain't never tol' you dat tale? Ef dey ain't got sense

'nuff fer ter tell you all de tales dey is gwine, you better sic de dogs on um an'

run um off de place — ef you got any dogs lef'."

"Well, they don't tell us any tales," said Buster John truly enough. "Old Aunt Free

Polly used to tell us some; but that 's been so long ago that we've forgotten them.

You ought not to have said anything about a tale if you did n't want to tell it."

Aunt Minervy Ann looked at the child and laughed. "Heyo, here!" she exclaimed. "Ef

dey 's gwine ter be any swellin' up an' gittin' mad, I'll tell de tale, and git 'way

fum here des quick ez I kin. I ain't come ter dis place fer ter git in no fuss."

The children composed themselves comfortably on the dead grass, and Aunt Minervy Ann

told the story of

BRER RABBIT AND THE

GOOBERS.

"Way back yander," said Aunt Minervy Ann, retying her head handkerchief, "de

times wid de

har1899.2007.001.024.jpg

creeturs wuz mighty much like dey is wid folks

now, speshually we-all up dar at de Perdue plantation . Dey wuz hard times.

I disremember whedder dey had been a war and de army swep' 'long, or whedder

dey wuz a dry drouth. Dey ain't much diffunce when craps fail.

"Well, anyhow, de times wuz mighty hard. Vittles wuz skacer dan hen's

tushes, an' dem what had it, hid it. An' ef dey ain't hide it, dey stayed

mighty close by it. Ol' Brer Rabbit wuz in jest ez bad fix ez any un um, ef

not wuss. Slick ez he wuz, he wa'n't slick nuff fer ter git sump'n ter eat

whar dey wa'n't none. De calamus patch gun out, all de saplin's had been

barked higher up dan Brer Rabbit kin reach, de tater patches wuz empty, an'

de pea vines wuz dry nuff fer ter ketch fire widout any he'p.

"So dar 'twuz. Like de common run er po' white folks, Brer Rabbit had a big

fam'ly. De young uns wuz constant a-cryin' 'Daddy! Daddy! fetch me sump'n

ter eat!' An' ol Mis' Rabbit wuz dribblin' at de mouf, she wuz dat

hongry.

"Ol' Brer Rabbit wuz so mad kaze he can't git no vittles nowhar and nohow,

dat he kicked a cheer 'cross de room wid his hin' foot and skeered de

har1899.2007.001.024.jpg

young uns so dat dey flipped

under de bed, an' dar dey stayed twel der daddy wuz out er sight an'

hearin'.

"Brer Rabbit knowed mighty well dat 'twa'n't gwine ter do fer him ter be

settin' roun' de house wid de fambly dat hongry dat dey can't skacely stan'

'lone. So he comb his hair, an' brush his hat, an' put on his mits fer ter

keep de sun fum frecklin' his han's, an' tuck down his walkin' cane, an' put

out down de road fer ter see what he kin see, an' hear what he kin

hear."

At this point the children laughed, Sweetest Susan convulsively, and Buster

John more sedately , yet heartily. Aunt Minervy Ann paused and regarded them

with grave, inquiring eyes.

"What de matter now?" she asked solemnly. At this the children laughed

louder than ever. "Well!" she cried, "ef you gwine ter have conniption fits,

I'll wait twel dey pass off."

"Why, I was laughing because you said Brother Rabbit put on his mits to keep

his hands from freckling," explained Buster John; and Sweetest Susan, when

she could catch her breath, declared that she was laughing for the same

reason.

"You-all must be mighty ticklish," remarked

har1899.2007.001.025.jpg

Aunt Minervy Ann, plucking at the dead grass. "I

ain't see nothin' funny in dat. You nee' n't think dat rabbits is like dey

uster be. Dey done had der day. In dem times dey growed big and had lots er

sense, an' dey wuz mighty keerful wid deyself. But dey done had der day.

Folks come 'long and tuck der place, an' since den dey done dwindle 'way

twel dey ain't nothin' mo' dan runts, an' skacely dat. Folks holdin' de

groun' now, but how long dey gwine ter hol' it? How long fo' sump'n else'll

come 'long an' take folks' place? De time may be short, er it may be long,

but it'll come — you min' what I tell you; an' when it do come, folks'll

dwindle 'way and git ter be runts des like de creeturs did, and dey'll

fergit how to talk so eve'ybody kin know what dey sayin'.

"Look at de creeturs! Why, de time wuz when dey could talk same ez folks,

but now dey can't hardly jabber, and dey ain't nobody know what dey sayin'

'cept 't is dish yer A'on you got here" — the children looked at each other

and smiled — "an' dat don't do him ner dem no good. Now des ez de creeturs

is, de folks 'll be when de time come — you mark my word!"

har1899.2007.001.025.jpg

"But all this time," remarked Buster John slyly, "the rabbits in the tale

are suffering mightily for something to eat."

"Dat's so, honey! I got so much on my min' dat I done clean fergit 'bout de

tale. I wuz thinkin' 'bout de time when we-all, white and black, would be

brung low. You'll have to scuzen me, sho. Well, den, Ol' Brer Rabbit put on

his mits and tuck down his walkin' cane, and went promenadin' down de big

road. Ef he met anybody, dey never could gess dat he wuz mighty nigh

famished, kaze he walk des es biggity es ef he des had de finest kinder

dinner. He went on, smoothin' down his mustashes, when who should he meet

but Brer Fox, wid a big basket on his arm.

"'Whar you been, Brer Fox?'

"'Loungin' roun'. Whar you gwine, Brer Rabbit?'

"'Up hill and down dale. What you got in yo' basket, Brer Fox?'

"'Des er hatful er goobers, Brer Rabbit.'

"'Parched, Brer Fox?'

"'Yes, indeedy, Brer Rabbit; parched good en brown.'

har1899.2007.001.026.jpg

"'No, I thank you, Brer Fox; none fer me. Ef dey wuz fresh an' raw now,

maybe I'd take some. But parched—my stomach won't stan' um. Mo' dan dat, I

des had a bait er groun'-squir'l.'

"Now, Brer Rabbit wuz hankerin' atter de goobers so bad dat he can't stan'

still, an' when he say groun'-squir'l, Brer Fox under-jaw drap an' 'gun ter

trimble an' quiver. He say: —

"'Wuz he fat, Brer Rabbit?'

"'Fat ez a butter-ball, Brer Fox, but not too fat; dey wuz plenty er lean

meat.'

"'My gracious, Brer Rabbit! Whar 'd you git 'im?'

"'Back up de road a piece, Brer Fox. A whole fambly un um stays dar.'

"'Show me de place, Brer Rabbit; my ol 'oman been hankerin' atter

groun'-squir'l fer de longest.'

"'I'll show you, Brer Fox; but yo' claws longer 'n mine, an' you'll hatter

do de grabblin' .'

"Brer Fox jaw shuck like he had a swamp chill. He 'low: 'You never is see

nobody grabble , Brer Rabbit, twel you see me.'

har1899.2007.001.026.jpg

"'I'll stan' by, Brer Fox, an' see it well done.'

"Now, Brer Rabbit did know whar dey wuz a burrow er some kin', but he ain't

know whedder it wuz a groun'-squir'l, er a wood-rat, er a highlan' moccasin.

So he tuck Brer Fox up de big road a piece, and den dey struck out thoo de

woods. But 'fo' dey start in de timber, Brer Rabbit 'low : —

"'You better hide yo' basket er goobers, Brer Fox, kaze it'll bother you ter

tote it thoo de bushes. I'll watch you grabble, and I'll keep my eye on de

basket.'

"So said, so done. Brer Fox sot de basket down in de bushes, an' dey kivered

it wid leaves and trash, and went on. Bimeby, dey got ter de place whar Brer

Rabbit say de fambly er de groun'-squir'l live, an' he show Brer Fox de mouf

er de burrow. Brer Fox 'low: —

"'It'll be hard diggin', Brer Rabbit.'

"'De harder de diggin', Brer Fox, de bigger de crap. Dat 's what I hear um

say.'

"Wid dat, Brer Fox shucked his coat, an' roll up his shirt-sleeves, an'

start ter diggin'. He made de dirt fly. Atter while he stop ter rest and

'low: —

har1899.2007.001.027.jpg

"'Keep yo' eye on my goobers, Brer Rabbit; don't let nobody run off wid um;'

and den he sot in ter grabblin agin.

"'I'll watch um, Brer Fox; don't make no doubt er dat.'

"Den Brer Rabbit run to whar de basket wuz, flung de trash off 'n it, tuck

it off in de woods a little piece, an' emptied all de goobers out 'n it. Den

he fill it up wid sticks and chips, mos' ter de top, and on de trash he put

a layer er goobers. Den he tuck it back and kivered it like twuz at fust,

and went ter whar Brer Fox was grabblin'. Brer Fox 'low: —

"'You smell mighty strong er parched goobers , Brer Rabbit.'

"'I don't doubt dat, Brer Fox; I lifted de lid er de basket, fer' ter see ef

dey wuz all dar, an' de stench fum um come mighty nigh knockin' me down. Fer

a minnit or mo' I wuz dat weak and sick I come mighty nigh gwine home.'

"Well, Brer Fox he grabble and grabble, twel he git tired er grabblin', and

den he 'low dat he b'lieve he'll put off eatin' any groun'-squir'l twel some

yuther day. Brer Rabbit say he kin do ez he please 'bout dat; an' den dey

went on back ter

har1899.2007.001.027.jpg

whar dey lef' de basket.

Brer Rabbit helt his nose an' lifted de lid an' looked in, an' 'low: —

"'Dey all dar, Brer Fox ; you kin look for yo'self.'

"'I don't 'spute it, Brer Rabbit; I ain't say dey ain't all dar.'

"'Dat may be, Brer Fox, but I hear folks say you mighty 'spicious, an' I

don't want nobody fer ter be 'spicionin' er me.'

"Brer Fox 'low: 'Don't kick fo' you er spurred, Brer Rabbit.'

"Brer Rabbit say, 'De right kinder horse don't need no spurrin', Brer

Fox.'

"Well, Brer Fox picked up his basket an' went on home, an' Brer Rabbit he

went de yuther way; but by de time Brer Fox git out er sight good, of Brer

Rabbit run home, an' git a basket, an' run back ter whar he done hid de

goobers, and 'twa'n't no time fo' he had um all at home, an' him an' his ol

'oman an' de chillun had a reg'lar feastin' time.

"When Brer Fox foun' dat he had mo' trash dan goobers in his basket, he was

dat mad dat he could 'a' bit hisse'f; but he ain't let on. He know dey ain't

no use makin' no fuss, an' he

har1899.2007.001.028.jpg

know mighty well dat he can't ketch Brer Rabbit ;

he done tried dat befo'.

"So dis time he went ter law 'bout it. He laid de case 'fo' 'ol Judge Wolf,

an' dey got out papers, an' sont atter Brer Rabbit. Well, dey want no

gittin' 'roun' dat. Brer Rabbit had ter go; he wuz mighty skittish, but he

knowed dat ef dey got de law on 'im he won't have no peace in dat

settlement. So he went ter court, and dar he foun' a whole passel er de

creeturs. When he got in, ol' Judge Wolf tuck his seat on de high flatform,

an' put on his specs, an' started ter readin' in a great big book. Dey

called de case, and Brer Fox tuck de stan' an' tol' his side; and den Brer

Rabbit got up an' tol' his side. Judge Wolf tuck off his specs an' look at

Brer Rabbit wid a broad grin. Den he ax Brer Fox how many goobers he had,

and Brer Fox say he dunno how many, but dey must 'a' been a bushel. Judge

Wolf ax 'im whar'bouts he got um. He say he got um frum a man on de

river.

"Judge Wolf 'low, 'A man on de river! Well, ef dat de case you must 'a' had

some sho 'nuff.' Den he turn ter Brer Rabbit an' 'low: 'Brer Rabbit, you'll

hatter pay 'im his goobers

har1899.2007.001.028.jpg

back when you dig yo' crap.'

Brer Rabbit say he'll do de best he kin.

"Judge Wolf say, 'How'll you have um, Brer Fox; raw er parched?'

Brer Fox holler out, 'Parched, parched!'

"Judge Wolf 'low, 'Brer Rabbit, when you dig yo' crap, save all de parched

goobers fer Brer Fox.'

"Brer Rabbit say he'll be mo' dan glad ter do so, an' den dey 'journed de

court-house."

"That's what I call stealing," said Sweetest Susan emphatically, as Aunt Minervy Ann

paused.

There was silence for awhile, and then Aunt Minervy Ann shook her head and said: "Ef

folks had 'a' done dat away 't would 'a' been stealin', but de creeturs — dey got

ways er dey own, honey. Dey dunno right fum wrong, an' ef dey did, 't would be mighty

bad for we-all. Our own hosses 'ud kick us, and our own cows 'ud hook us, forty times

a day. Dey would n't be no gittin' 'long wid um de way dey er treated."

"That's so," said Buster John.

Just then Major Perdue came out on the back porch of the big house and called Aunt

Minervy

har1899.2007.001.029.jpg

Ann. It turned out that the two extra mules in the lot did belong to the major. He

borrowed some harness and a wagon, and drove home with plenty of provisions, and with

a comfortable sum of money which the children's grandfather had loaned him. Aunt

Minervy Ann carried her cart back empty, but she did n't mind that. The children rode

with her a little piece, and as a result had a very peculiar experience.

har1899.2007.001.029.jpg

III.

A STRANGE WAGONER

Major Perdue lived in the

direction of the village, a few miles away, and when Buster John and Sweetest Susan

clambered on Aunt Minervy Ann's ox cart, they shouted to their grandfather, the

White-Haired Master, that they were going to town and did n't know when they would

return. But as it happened, they were to return very soon, for they had gone only a

short distance before they met a covered wagon, drawn by two large fat mules. The

driver was a white man, with a very red face and eyes as small and as restless as a

mink's. He had sandy hair, mixed with gray, and he wore a faded gray uniform. When he

saw Aunt Minervy Ann and the children he began to sing, but, in spite of the singing,

which grew louder as he came nearer, Buster John and Sweetest Susan thought they

heard a child crying and sobbing when the two vehicles passed each

har1899.2007.001.030.jpg

other. Aunt Minervy Ann was sure she heard it, and she declared that there was

something wrong about the man; she could tell by his peculiar appearance.

So she advised the children to jump down and follow the wagon as far as their gate if

no farther. They might find out something and be able to do somebody a good turn.

Sweetest Susan did n't see the necessity of this, but Buster John was keen for

anything that seemed to promise an adventure . He jumped from the cart and ran back

after the wagon, while Sweetest Susan followed more leisurely. She followed fast

enough, however , to catch up with the covered wagon, which was not going very

rapidly. The wagon was the kind used by the North Carolina tobacco pedlers. The cover

was higher at the ends than in the middle . The pole stuck out behind, and a water

bucket was fastened to it. A trough for feeding the mules was swinging across the

rear, and this with the jutting pole enabled Buster John to climb up and peer into

the wagon. At first he saw nothing but a lot of bedclothes piled up on some bundles

of fodder; but presently he heard sobbing again, and, looking closer, he saw a little

child lying on its face in an attitude of despair.

har1899.2007.001.030.jpg

At first Buster John thought of crawling into the wagon and asking the child what

ailed it, but the man who was driving was in plain view, and, though Buster John was

bold enough for a small boy, he was cautious too. The child seemed to be not more

than two or three years old, and as it had on a frock Buster John could n't tell

whether it was a boy or a girl. While he was considering what to do, the child raised

its head, saw him, and wailed: "Oh, p'ease tate me out er here!" Buster John fell

rather than jumped down, for he was afraid the man would see him. Presently the face

of the child appeared at the back part of the wagon. At first it seemed that the

little creature was preparing to jump out, but either fear overcame it, or the driver

reached back and cut it with his whip, for it fell back with a loud wail of agony, a

wail that sounded like the cry of some wild animal.

Sweetest Susan was ready to cry, her sympathies were so keen, but Buster John was

angry. He ran to the front of the wagon and yelled at the man: —

"What's the matter with your baby?"

"Hey?" responded the man. "Want a ride?

har1899.2007.001.031.jpg

Of course you can ride; climb up. I ain't got time to stop."

"I said what's the matter with the baby, the baby in the wagon?" cried Buster John at

the top of his voice.

"In the waggin? Oh, yes! Well, get in."

"Don't you do it, brother," said Sweetest Susan . "He heard what you said."

The man looked at them with twinkling eyes. "Oh, both want to ride. Well, get in —

that 's all I've got to say."

Buster John was not to be put down that way; he was very close to home now; in fact,

he could see the tall form of his grandfather standing on the knoll above the spring,

watching the covered wagon with curious eyes, for it had been a long day since one

had come along that road going in that direction. So Buster John grew very bold

indeed. He went close to the front wheel of the wagon, close to the heels of the

off-mule.

"You know what I said. I asked you what was the matter with the baby in the

wagon."

The man seemed to rouse himself. "Baby in the waggin! Why, they ain't no baby in

there; it's a cat I picked up on the way. She 's a mouser. We need mousers where I 'm

agoin'."

har1899.2007.001.031.jpg

Buster John, more indignant than ever, ran ahead, called his grandfather, and asked

him to go and see about the baby in the wagon, telling him hurriedly how queerly the

man had acted.

But the White-Haired Master shook his head. "He's only playing with you," he

said.

The children were in despair at this, for they were sure that something was wrong.

Even Aunt Minervy Ann had said so. Buster John began to pout, and Sweetest Susan was

ready to cry. She looked appealingly at her grandfather, her eyes swimming in

tears.

"What is it, Sweetest?" the White-Haired Master inquired.

"That poor little baby," she said, controlling herself the best she could; "I'll

dream about it all night."

"Well, don 't cry; we'll see about it," remarked the grandfather soothingly.

By this time the wagon had come up. The driver bowed politely and would have gone on,

but the White-Haired Master motioned him to stop. This he did, but with no good

grace. He pulled up his mules, and sat on the seat expectantly , with a grin in his

face that was half a scowl.

har1899.2007.001.032.jpg

"You come from Milledgeville way?" the children's grandfather inquired.

"Who told you?" the man asked quickly; "them children there?"

"No," said the White-Haired Master, frowning a little. "I was simply inquiring."

The man laughed. "Well, I come from that- a-way."

"What news?" asked the White-Haired Master .

"Lots an' lots; I could n't tell you in a week. The wide world is turned end up'ards.

Murderin', riot, bloodshed, burnin', rippin', rarin', roarin', snortin'. You know

what?" The man closed his restless, roving eyes. "Well, down you way they're t'arin'

up the railroad tracks while the brass ban' plays. I ketched 'em a doin' of it, an' I

danced wi' 'em 'roun' the fire a time or two, an' then I picked up this waggin and

mules and come on 'bout my business."

The man wagged his head up and down, and rolled it from side to side, and shifted his

glances, and giggled in a very excited manner. The children's grandfather tried to

find some basis for the man's strange actions; tried to duplicate them in his memory,

but failed. Then he asked: —

har1899.2007.001.032.jpg

"What have you in your wagon?"

"Well, fust an' last, I've got some few bedcloze , an' some few ruffage for the

mules; an' then — well, yes, there's a cat I picked up, a reg'ler mouser. She growls,

but there ain't nothin' the matter wi' 'er."

In response to this statement the wagon cover was lifted high enough for the child to

put its head out. Its little face was distorted with fear or despair.

"Me ain't no tat!" it cried; "my mammy say I'm her 'itty bitsy baby; my daddy say I

'm his big 'itty man; my nunkey tall me Billy Bistit. Oh, p'ease lift me outer here.

Me wanter see my daddy an' mammy!" The child had cried and screamed so much that its

voice had a harsh and unnatural sound. It pierced the tender heart of the

White-Haired Master like a knife and roused him to a fury of indignation.

"Is that what you call a cat, you trifling scoundrel ?" he cried. He passed through

the gate and was now close to the man.

"That's what," answered the man with a chuckle. "He'll bite, an' he'll scratch, an'

he'll growl. An' he calls himself Billy Biscuit, but do

har1899.2007.001.033.jpg

he look like a biscuit? You would n't want me to call him a chicken, would you?"

He stuck out his tongue as he said this, and looked about as foolish as it is

possible for a grown man to appear, and the grandfather's indignation changed to a

feeling of amazement and disgust.

"Is the child yours?" he asked.

"Why, whose should he be, Mister? You'd be errytated ef you wuz a youngster an' had

to ride all day in a kivered waggin; now would n't you?"

The observation was a just one, considering the source; and though it lacked feeling

and sympathy, the White-Haired Master could make no reply.

"This is a likely place to camp — in there by the spring," the man remarked. "Ef I

thought I mought be so bold as to ax you" —

"You may," said the White-Haired Master. "Drive in the gate here and unhitch under

the trees yonder. There's fire under the wash-pot. You'll find plenty of wood to

start it up, but be careful about it; don't burn any of the fencing."

The man drove in as directed, turned his wagon round, the tongue pointing to the

gate, unhitched his mules, watered them without taking the

har1899.2007.001.033.jpg

harness off, and then gave them two

bundles of fodder apiece to munch on. Then he got out his frying-pan, his skillet,

and his coffee-pot, and finally proceeded to kindle a fire.

Buster John and Sweetest Susan watched all these proceedings with great interest,

especially as the man paused every now and then to talk to himself. "Yes, that 's

me," he declared over and over again; "Roby Ransom, corridor 1, room 9."

He paid no attention to Buster John and Sweetest Susan, nor to Drusilla, who joined

them as the wagon drove in the gate; and he seemed to have forgotten the child in the

wagon. But Sweetest Susan had not forgotten it. She stood by the wagon and saw the

little one looking at the man with frightened eyes.

The whole affair was very interesting to the children. The big trees had been a

favorite resort for campers in old times, and the youngsters vaguely remembered

seeing strange men sitting around the fire frying bacon that sent forth a very savory

odor, but of late years there had been no campers there. The campers and wagoners,

like most of the able-bodied men, had been camping out under the tents of the army or

sleeping, as

har1899.2007.001.034.jpg

Johnny Bapter put it, "under the naked canopies ." Therefore this mysterious man was

the first camper who had kindled a fire in the spring lot since Buster John, Sweetest

Susan, and Drusilla had been of an age to appreciate the circumstance.

Consequently they watched him closely and in comparative silence, their comments

being confined to low whispers. Sweetest Susan's solicitude was for the child in the

wagon, but her curiosity compelled her to keep sharp eyes on the man, who went

nervously about his business, and very awkwardly , too, as even the children could

see. Sweetest Susan's solicitude was rewarded, for, as she leaned against the frame

of the wagon, the child on the inside reached its soft little hands out and patted

her gently on the arm. To Sweetest Susan this was more than a caress, and she seized

the small hand and held it against her cheek for a moment. Then she made bold to ask

the man — she called him Mr. Ransom at a venture — if she might bring the little one

some supper.

"Who told you my name?" the man asked with suspicion in his eyes.

har1899.2007.001.034.jpg

"I heard you call yourself Roby Ransom," replied Sweetest Susan very politely.

"Well, you heard right for once," he said. "Supper for the young-un? Tooby shore;

fetch it. I did n't allow I'd take in boarders when I started, an' I ain't got any

too much vittles for myself."

So Sweetest Susan and Drusilla went to the house to arrange for bringing the child

some supper , while Buster John lagged behind and watched the man till the bell rang.

Meanwhile the grandfather had told his daughter (the mother of Buster John and

Sweetest Susan) about the child in the wagon, and that lady was in quite a fume about

it. At first she insisted on going down and taking the child away from the man; she

was sure there was something wrong.

"There may be," said the White-Haired Master , "but we are not sure about it, and we

might make bad matters worse. There's plainly something wrong about the man; that

much is certain; but the child may be his, and it may be badly spoiled. No, it would

be wrong to interfere with him; I've thought it all over."

"If you'll take my advice," remarked his

har1899.2007.001.035.jpg

daughter, "you'll make the negroes tie the man and lock him in the corn-crib until we

find out something about him."

"That would hardly be legal," said the old gentleman.

"Well, I don't think there is much law in the country at this time," the lady

insisted. "If we knew he had stolen the child, what could you do with him?"

"What you say is very true," remarked the White-Haired Master; "truer even than you

think it is. Still, there is no reason why we should be hasty and unjust."

As the lady was convinced against her will, she remained of the same opinion still,

and that opinion became a conviction when Sweetest Susan arrived and told all she saw

and all she thought. But there was nothing to be done but to give the child one full

meal if it got no more, and so the lady set about fixing supper for the unfortunate.

She piled a plate high with biscuits and ham and chicken, and when the children were

through supper they waited patiently for Drusilla to finish hers, so they could all

go together. Sweetest Susan insisted on carrying the plate herself.

har1899.2007.001.035.jpg

When they arrived at the camper's fire, they found the man eating supper by

himself.

"Where's the baby?" asked Sweetest Susan.

"In the waggin," replied the man curtly. "I wanted to take the imp out, but he would

n't let me tetch him. Git him out, if you can."

The child needed no coaxing when Sweetest Susan called him. He crawled to the front

of the wagon and held out his arms to her, and he hugged her so tightly around the

neck that it was as much as she could do to climb down without falling. The little

fellow was well dressed, but he was barefooted, and his feet were very cold.

"Where are his shoes?" asked Sweetest Susan indignantly.

"He must er pulled 'em off and flung 'em away. Oh, he 's a livin' terror, he is.

Don't you let him fool you."

The child ate his supper sitting in Sweetest Susan's lap, and he seemed to be very

hungry. He tried to make Sweetest Susan eat some, too, and once or twice he smiled

when she pretended to be eating ravenously. But for the most part the child kept his

eyes fixed on Mr. Ransom, and

har1899.2007.001.036.jpg

clung more tightly to Sweetest Susan whenever he caught the man looking at him.

The result of it all was, that when the time came for the children to go to the

house, Sweetest Susan found it impossible to get rid of the child. He would n't allow

Ransom to take him — he seemed ready to go into convulsions whenever the man

approached; and, finally, in order to induce him to get into the wagon, Sweetest

Susan had to go in with him (accompanied by Drusilla) and once there, she was

compelled to lie by the child until it dropped off to sleep. He held her hand tightly

clasped in his tiny fists.

Buster John was impatient, and said he was going to bed, and Sweetest Susan told him

to tell mamma that she and Drusilla would come as soon as the baby went to sleep.

Drusilla, drowsy-eyed, lay down on the bedclothes and was asleep bfore the child was.

Sweetest Susan made every effort to withdraw her hand and slip from the wagon, but

these movements aroused the child, and set it to whimpering.

Everything was very still; even the frogs called to one another drowsily. The mules

had cleaned up their ration of fodder, and were now dozing.

har1899.2007.001.036.jpg

Under these circumstances, it was not

long before Sweetest Susan was as sound asleep as Drusilla, and, apparently, the

child was asleep, too.

Ransom in due time arose from the fire where he had been sitting, went to the rear of

the wagon, looked in, and then stood listening intently. Nothing was to be heard but

the regular, heavy breathing of three sound sleepers. He went to the spring, got some

water, and carefully put out the fire. At no time had it been a large one. Then

stealthily, almost noiselessly, he hitched the mules to the wagon, drove out at the

gate and into the public road. Once Sweetest Susan dreamed that she was going to town

in the wagon with Johnny Bapter; but that must have been when the wagon was going

down the long and steep hill that led to Crooked Creek.

An hour after the wagon had disappeared, Mrs. Wyche, the children's mother, aroused

herself from thoughts of her husband, who was in the army, and remembered that it was

long past the time for Sweetest Susan to be in bed. She called to Jemimy, Drusilla's

mother, who was nodding by the fire in the dining-room.

"Jemimy, go to the spring where the wagoner

har1899.2007.001.037.jpg

is camping, and tell Sweetest Susan and Drusilla to come straight to the house; they

should have been here long ago. Bring them with you."

Jemimy went to the spring, but saw no wagon nor any signs of one, the fire being out.

She heard Johnny Bapter singing near the lot; she called him and asked about the

wagon.

"Ef 'tain't down dar by de spring, I dunner whar 't is."

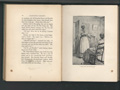

Jemimy ran back to the house, nearly frightened to death. Her report was: "Mist'iss,

dey ain't no wagon dar!"

"Merciful heavens!" screamed the lady, "I told father to have the man tied and locked

in the corn-crib, and now he has stolen my child! Oh, what shall I do?"

"An' he got Drusilla!" cried Jemimy, throwing up her hands wildly.

The White-Haired Master came forth from the library with a troubled face. He was a

man of action, and in five minutes the whole plantation was aroused. But Sweetest

Susan and Drusilla had disappeared. Strong-lunged negroes called them, but they made

no answer. They were several miles away and fast asleep.

har1899.2007.001.037.jpg

[illustration - "DEY AIN'T NO WAGON DAR!" ]

har1899.2007.001.038.jpg

har1899.2007.001.038.jpg

IV.

SWEETEST SUSAN'S STRANGE ADVENTURE.

The White-Haired Master was a man of action, but one was

before him. As soon as Johnny Bapter heard Jemimy's inquiry, and found that the wagon

had disappeared, he ran to Aaron's cabin with the news. Instantly the Son of Ben Ali

was on his feet and running. Straight to the horse-lot he went, where he gave a

peculiar call, and one of the horses came galloping to him, whinnying. There was a

clinking of harness , a rush to the carriage house, and in two minutes the rattle of

buggy wheels was heard on the gravel. By the time the White-Haired Master could get

his overcoat on and fix himself for facing the cold, crisp air, the buggy was at the

back gate with Aaron calling, "All ready, Master."

He had no need to repeat the call. The children's grandfather came running down the

steps

har1899.2007.001.039.jpg

very nimbly for one of his years, and in a moment was in the buggy, with Aaron beside

him.

"Are you going?" he asked.

"Yes, Master," replied the son of Ben Ali.

"I'm mighty glad of it," remarked the White-Haired Master. "Where are the reins?"

"In the saddle ring; I forgot to take 'em out." He spoke to the horse, and the animal

broke from a walk into a canter, shaking its head playfully . By this time, Johnny

Bapter, armed with a flaming torch, was more than halfway to the side gate, where the

wagon had come in and gone out. He reached the gate as the buggy drove up, and Aaron

seized the torch and examined the ground. He saw the wagon tracks coming in, and saw

where it turned as it went out. He spoke to the horse as he flung the torch away, and

climbed into the buggy as it moved off. He spoke once more, and the animal broke into

what seemed to be a wild gallop, going so rapidly that the buggy appeared to be in

the air when it went whirling over a sunken place in the road. On level stretches the

horse ran as a racer runs, and the wheels of the buggy gave forth an undertone that

sounded like the droning of a swarm of bees.

har1899.2007.001.039.jpg

"How do you drive without the lines?" the White-Haired Master asked, when he became

convinced that the son of Ben Ali had the horse under complete control.

"He knows me, Master, and I know him," replied Aaron.

It was not a satisfactory answer, perhaps, but it seemed to be sufficient. Up hill

the horse, which was a strong one, went with a long, swinging trot. The top reached,

the trot would be exchanged for a gallop. This went on for some time, until Aaron

vetoed the gallop. When they had gone on for an hour, and were nearly to Harmony

Grove, a small settlement about ten miles from the Abercrombie place, the Son of Ben

Ali stopped the horse, jumped from the buggy, and carefully examined the road ahead,

getting down on his hands and knees to do so.

He rose and shook his head, and walked slowly back to the buggy.

"What is the matter?" the White-Haired Master asked.

"The wagon ain't come 'long here, Master. The wheel tire is two inches wide. No track

like that in the road."

har1899.2007.001.040.jpg

"It was an army wagon," said the grandfather musingly. "What has become of it? It

must have passed here. The first fork in the road is at Harmony Grove. We'll go

there."

So they drove on to Harmony Grove. As it happened there was a sort of social

gathering in the schoolhouse. As always happens on such occasions , there were

several young men and boys who were too shy to venture in the house where the girls

and young women were. If a wagon or vehicle of any kind had passed, they surely would

have seen it. But no wagon had passed.

Such of them as had horses volunteered to join the searching party, but the

White-Haired Master thanked them. If the wagon had n't passed, it was still on the

road somewhere, and he and Aaron would find it. Indeed, the White-Haired Master had

made a calculation. Harmony Grove was ten miles from his place. He had come the

distance in something less than an hour, and it was now ten o'clock. If the wagon had

left the spring at eight o'clock it could hardly have reached Harmony Grove before

then. Aaron judged that they should have overtaken the wagon about six miles from the

spring.

har1899.2007.001.040.jpg

As a matter of fact, they had overtaken the wagon and passed it, five and one half

miles from home, or, to be more exact, at the humble residence of Mr. Barlow Bobs.

They had passed the wagon without knowing it, for the reason that the vehicle was not

in sight from the road, and they would have passed it in broad daylight.

The driver, Mr. Roby Ransom — that was really his name, as it turned out — had not

gone more than two miles from the Abercrombie place before the desire to sleep

overcame him, and he began to nod. For a while he would nod, and then rouse himself;

but finally he leaned against the framework, over which the cover was spread, and

began to sleep soundly. The lines slipped from his hands, but caught on the brake and

hung there, too high for the feet of the mules to become entangled in them.

When the wagon came to the top of the long hill that slopes down to Crooked Creek,

the mules were surprised to feel no restraining hands on the reins. At first they

hardly knew what to do, but they were well trained, and they held back the wagon

until near the bottom, and then they broke into a swift trot and went swishing

through the

har1899.2007.001.041.jpg

shallow waters of Crooked Creek. Without a pause they pulled the wagon sedately up

the opposite hill, which was not a very steep one. They remained in the road as

became sensible mules, but they grew more and more uncertain in their movements as

they realized that no hand was guiding them.

Finally they came to the humble home of Mr. Bobs — or, rather, they came to the short

lane that led to Mr. Bobs's log cabin. Into this they turned, the hub of the hind

wheel missing the fence corner by the breadth of a hair. Pursuing this road, they

followed it into Mr. Bobs's back yard; and they finally drew up behind the corn-crib,

a double-pen built of logs. As there was a fat fodder stack behind this crib, the

mules concluded that they would put up for the night. After this, the only movement

they made was to see-saw the wagon as they reached for the fodder, and to snort

occasionally when too much dust from the forage crept up their nostrils.

Once, about five minutes after the mules had reached this harbor, they pricked up

their ears at the sound of a running horse whirling a buggy along the road, and Mr.

Bobs's house-dog barked

har1899.2007.001.041.jpg

dubiously, but beyond this there was

nothing to bother them, and no alarming noises were heard. Sweetest Susan, Little

Biscuit, and Drusilla were sound asleep, and so was Mr. Roby Ransom. It was a good

thing for Mr. Ransom that he was asleep, for there is no doubt that if the

White-Haired Master had come up with him on the road he would have fared but ill. But

Providence seemed to have taken him under its wing.

The White-Haired Master concluded to wait in the neighborhood of Harmony Grove until

dawn, knowing that nothing could be done in the darkness . It was a long, long night.

The grandfather walked up and down, up and down, the whole time, and though the Son

of Ben Ali sat in the schoolhouse as still as a statue, he was as impatient as the

Master. He had built a fire in the old sheet-iron stove, and the draft rushing into

this puffed like a locomotive, and, for a while, kept time with the tramp, tramp,

tramp, of the grandfather.

But dawn came at last, and as soon as things were visible, the two were in the buggy

and away. When they had gone two or three miles toward home, Aaron jumped from the

buggy and

har1899.2007.001.042.jpg

strolled on ahead of the horse. It was quite light by this time, and he scanned the

road carefully , searching for the tracks made by the big wheels of the army wagon.

He could not find them where they were not, but when he came to the short lane that

led to Mr. Bobs's house, he saw where the wagon had turned in. Making sure that it

had not come out again, he waited for the White-Haired Master to come up. He said not

a word, but pointed to the tracks made by the wheels.

Now, it happened that Mr. Bobs had his sister, Miss Elviry, for his housekeeper. Miss

Elviry was forty-odd years old, and quite independent of servants, and it was her

habit to rise at daybreak, summer and winter, kindle into a blaze the fire that had

been wrapped in a blanket of ashes the night before, and proceed to cook an early

breakfast , so that her brother might get to work at his turning-lathe, or his

broom-making, as soon as possible. Miss Elviry went to bed early and rose early, as a

matter of both conscience and habit. But on this particular morning she rose earlier

than usual. She had a "feelin'," as she afterward expressed it, that everything was

not all

har1899.2007.001.042.jpg

right. Once or twice, when she woke

during the night, she heard the house dog uttering smothered growls and whining, a

certain sign that everything was not as it should be. She refrained from rousing her

brother, but she had a good mind to. She made up for her restraint in this matter,

however, by rising half an hour earlier herself . She kindled a fire, put on a supply

of wood to keep it going, and hurriedly dressed herself. Then, although the stars

were shining, she unbolted the back door and looked out. The little outhouse in which

Mr. Bobs did his work and kept his tools barred her vision, but she heard unusual

noises, such as the rattling of chains and the creaking of harness and the snorting

of horses or mules.

Now, Miss Elviry was not a timid woman. She had some of the independence and energy

that would have made her brother more prosperous had he possessed a fair share of

them. So, while she was astonished at the noises she heard, she was not alarmed.

Instead of rushing into her brother's room to arouse him, she seized the axe, which

was always brought in over night in case of an emergency, and sallied out to see what

it was that had taken possession.

har1899.2007.001.043.jpg

The house dog heard her, and came out from under the house fairly screaming with

delight, for he had had a horrible night of it. Feeling himself adequately reinforced

by Miss Elviry's presence , his bristles rose, and he rushed around the outhouse and

proceeded to bay the back end of the wagon with the greatest fury, and his

indignation grew even greater when he heard Miss Elviry's firm voice urging him to

"Sic 'em, Spot! Sic 'em!"

The voice aroused Sweetest Susan, but did not seem to disturb the other sleepers. The

child rubbed her eyes, but for a long moment she could not imagine where she was.

Then she remembered she was in the wagon when she should be at home in bed. And, "Oh,

what will mamma say?" Dawn, still glimmering far away, sent a gleam of light into the

wagon, and toward this Sweetest Susan groped her way, stumbling over Drusilla, who

merely turned over with a sigh that sounded like a groan.

"Who are you, anyhow?" cried Miss Elviry sharply.

"Oh, it's only me!" answered Sweetest Susan, whose head and shoulders were dimly

outlined

har1899.2007.001.043.jpg

[illustration - "OH, WHAT WILL MAMMA SAY?" ]

har1899.2007.001.044.jpg

har1899.2007.001.044.jpg

against the interior darkness of the

wagon. "Take me out please. Oh, this is not home! Where am I?"

Miss Elviry went nearer; there was something about the child's voice that drew her.

"Oh, hush up, Spot!" she cried to the dog; "now you've started, you'll never stop."

She went close to the wagon end and looked at the child as well as she could. "What's

your name, honey?"

Now, as soon as Miss Elviry came nearer, the child's sharper vision recognized her.

She made quilts, and wove counterpanes for people who were comfortably well off, and

she had in this way been a frequent visitor at the Abercrombie place.

"Is that you, Miss Elviry? Please take me out!"

Miss Elviry was thunderstruck, as she said afterwards.

"Well, ef that ain't—Why! Well I know the end of the world ain't fur off now! Susan

Wyche, what are you doin' in this rig at this time of day, when by good rights you

ought to be at home in bed?"

"Take me out, please, Miss Elviry; and don't

har1899.2007.001.045.jpg

scold. I 'm going to run to the house as hard as I can."

"Ef you are talkin' about your own house, you'll have to do some extry hard runnin'

ef you get there by dinner time. You'll go into this house right here. 'T ain't so

big an' fine, but the fire in there is just as warm, and your hands are like

ice."

So she carried Sweetest Susan in the house, put a pillow in the chair, "to make it

feel like home," as she said, and stationed the child in the warmest corner. Then she

woke her brother. "Do your dressin' in your own room," she said; "we've got comp'ny

this mornin'."

Mr. Bobs did n't seem to relish this, and he began to grumble in tones too low to be